"Stacking Traumas": Communicating Sound, Negotiating Trauma

Introduction

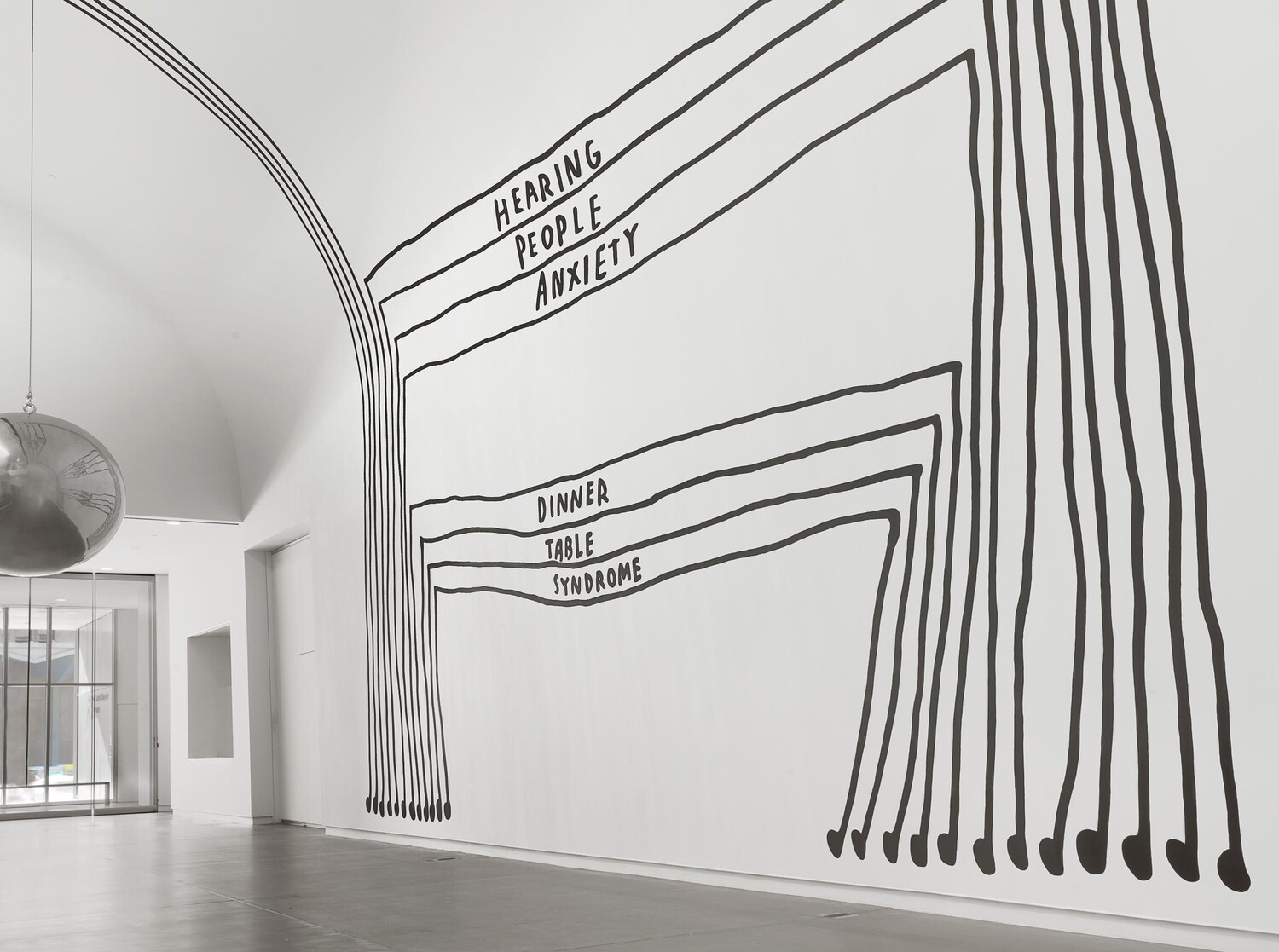

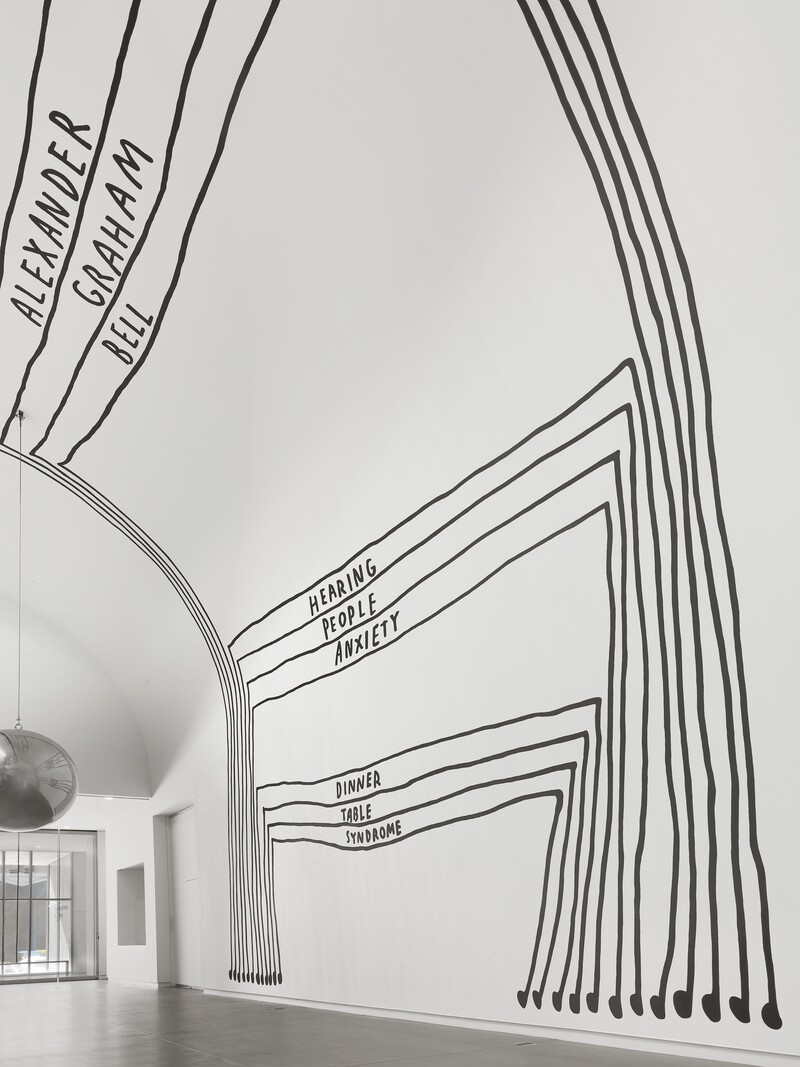

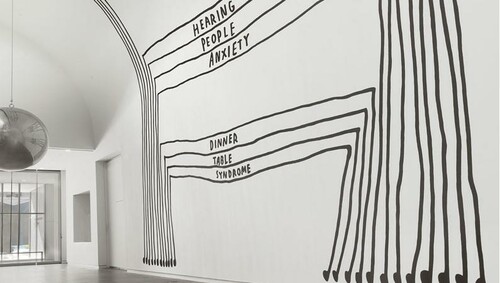

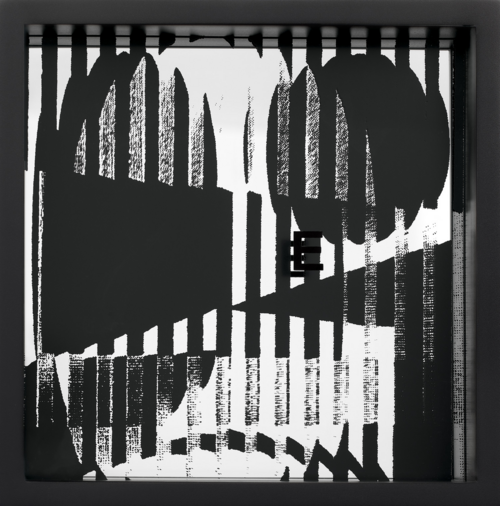

This guide explores Stacking Traumas, the site-specific mural by Christine Sun Kim on view at the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum from January 25, 2021–January 31, 2022.

"My art practice mainly deals with socially informed ideas surrounding sound, and that entails processes of what I have called ‘unlearning sound etiquette’ and challenging ‘vocal authorities.’" — Christine Sun Kim

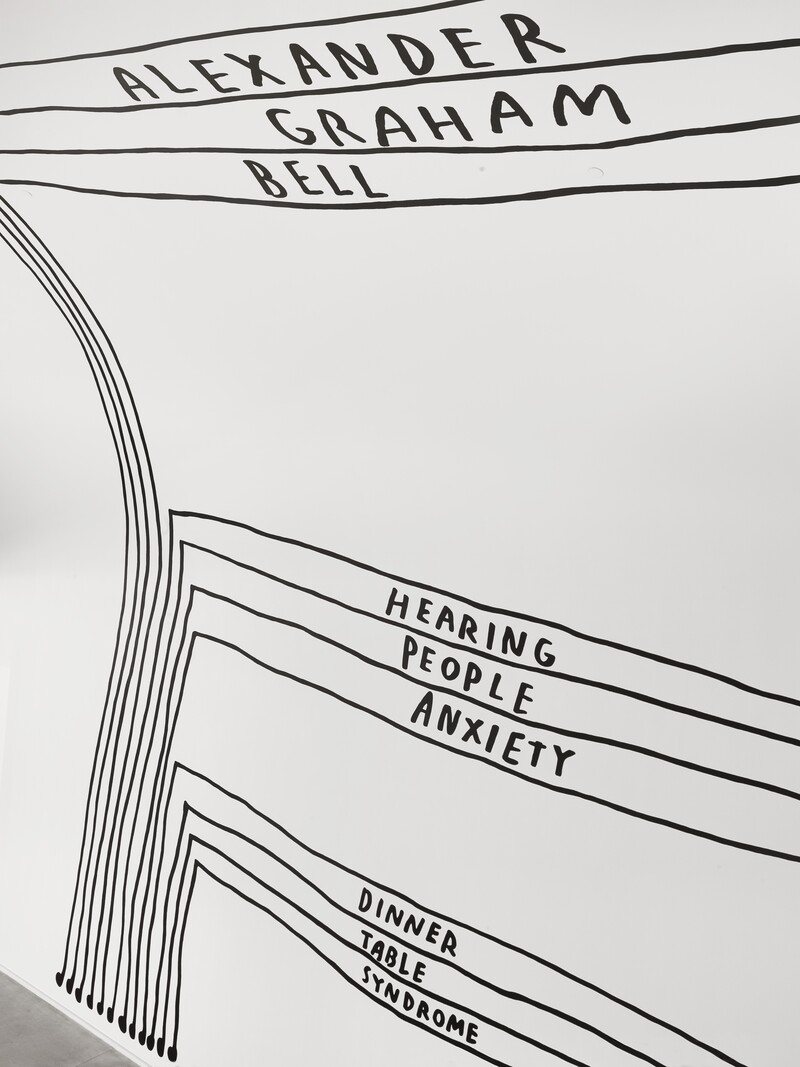

The multidisciplinary artist and activist Christine Sun Kim (b. 1980) explores concepts of sound and how it is valued in society from her perspective as part of the Deaf community. She often creates diagrammatic drawings that incorporate communication systems such as American Sign Language (ASL) and musical notation to examine sound as visual representation and as different states of emotion. In Stacking Traumas Kim identifies three sources of trauma for Deaf people: Dinner Table Syndrome, Hearing People Anxiety, and Alexander Graham Bell. Adapted from a drawing, the twenty-five-foot mural scales the curved wall of the Kemper Art Museum’s Saligman Family Atrium.

This guide also explores Stacking Traumas in relation to other recent works by Christine Sun Kim. Rooted in both the historic and the contemporary, Kim deploys a subversive wit to call attention to obstacles the Deaf community faces and to celebrate Deaf culture. Her explicitly personal and political works are an entry point into a broader dialogue about Deaf culture, the systemic marginalization of the Deaf community, and accessibility in the arts.

A Closer Look

To begin our exploration, let’s start by examining Stacking Traumas as a site-specific work designed intentionally for the Museum’s atrium. As you view the installation images above, consider how the relationship between the mural and the atrium’s space shapes your responses. As you look, take note of the formal elements, including the use of text.

"Like sound, ASL cannot be captured on paper; thus, I combined these various systems in an attempt to open up a new space of authority/ownership and rearrange hierarchies of information." — Christine Sun Kim

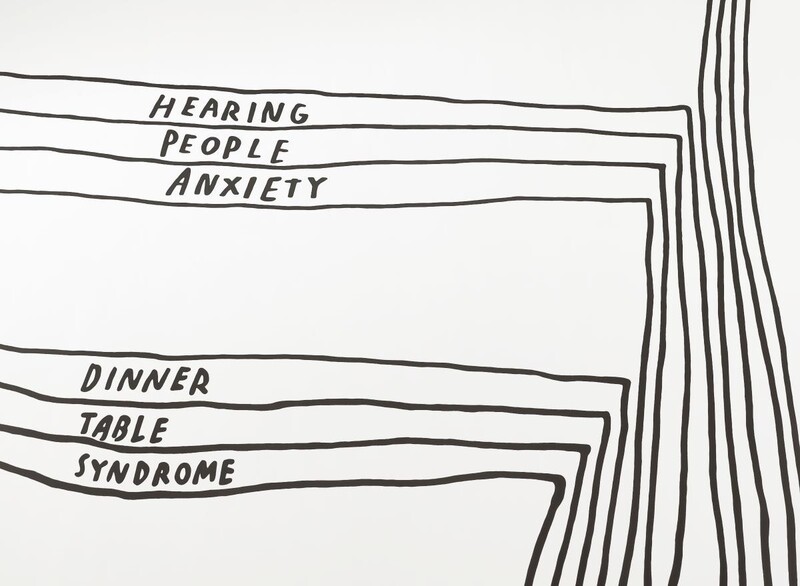

In Stacking Traumas three tables positioned on top of one another are formed by elongated lines that double as musical notes. The horizontal lines of each table reference beams used in musical notation. Beams connect the stems of consecutive notes to form a rhythmic grouping, making sheet music easier to read. Kim’s extended horizontal lines also recall the musical staff in sheet music, in which a set of five horizontal lines represent different levels of pitch. Here the four horizontal lines also suggest the word “score,” which is signed in ASL with four fingers. While fluid in form, the repetition of the notes suggests an echo, bringing to mind the reverberating effects of sound.

Kim’s layered references to music invite us to consider musical notation as both a visualization of sound and a language of communication. In doing so, the mural explores the relationship between musical notation and ASL, both visual-spatial sign systems that require specific training to access their meaning. The juxtaposition of text and visual language challenges spoken language’s position within the communication hierarchy, shifting the burden of translation onto the non-signing viewer.

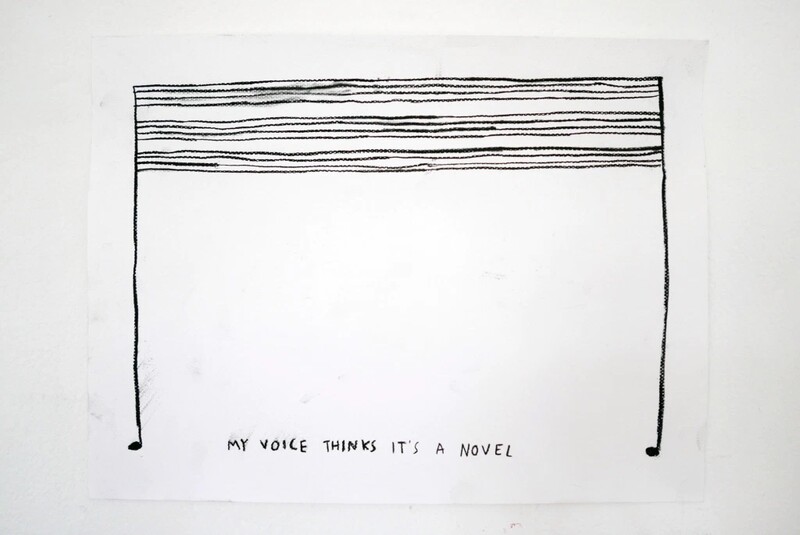

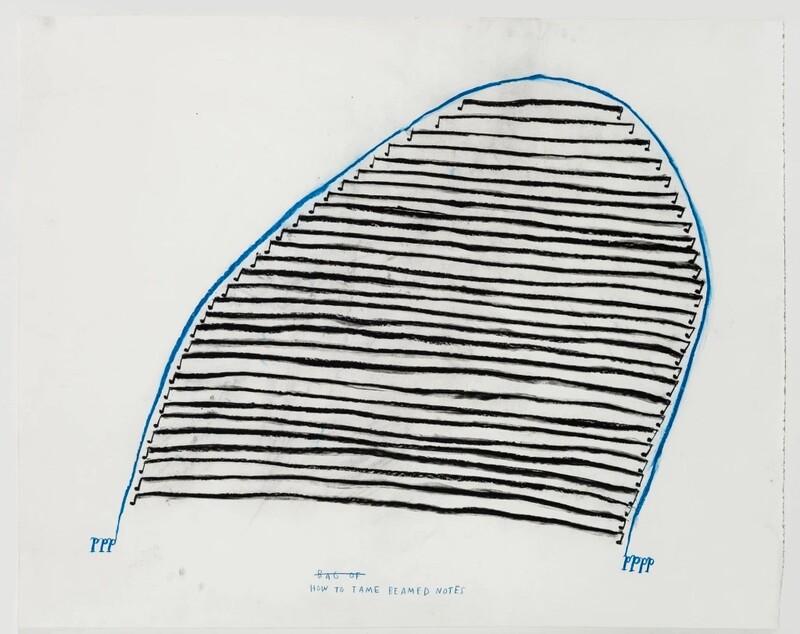

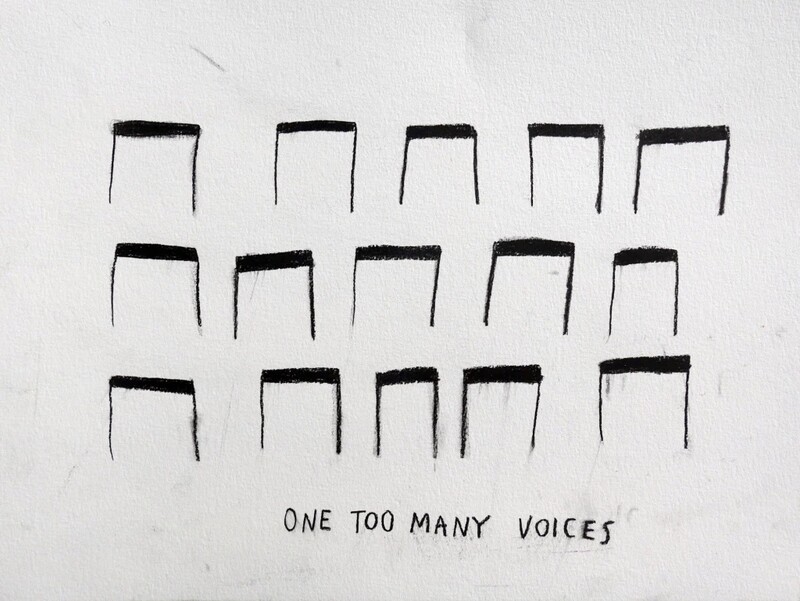

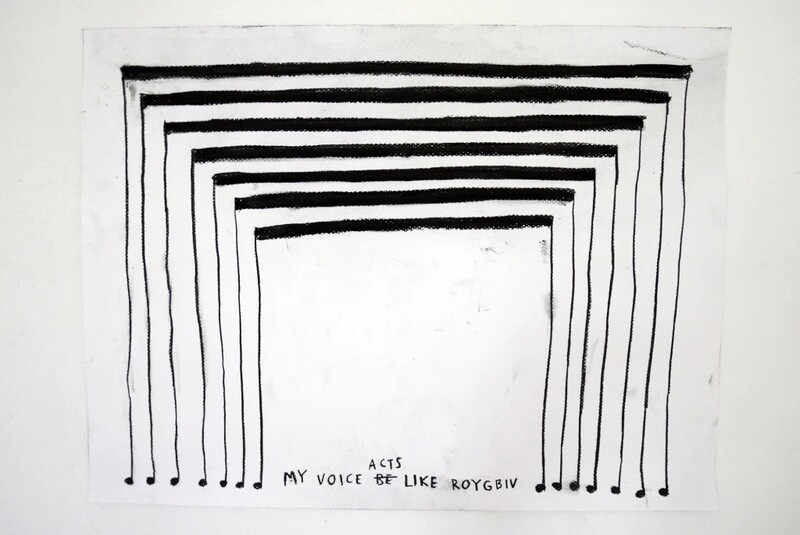

Let’s take a moment to look at some other works by Kim that incorporate musical notation. As you consider these drawings in relationship to Stacking Traumas, take note of the visual similarities and differences.

The drawings paired with text point to the many ways Kim’s voice can be both represented and misrepresented through ASL interpretation and televisual captioning services that often fail to capture the range and subtleties of signed communication. For Kim, working with ASL interpreters shares affinities with musical notation. She has described her voice as the score, herself as the conductor, and the interpreter as the performance. The collaborative process of working with ASL interpreters requires trust in how her voice is represented and by whom in different social contexts. By adapting musical notation to convey the complex dynamic of interpretation between the languages of ASL and English, Kim’s drawings underscore the relationship between sound and identity.

"By putting ASL in music format, suddenly language has a voice all of its own. In these drawings, I explore the different voices I have worked with and my experience with sound." — Christine Sun Kim

In Stacking Traumas, art, sound, and the social currency of language practices intersect at three points of trauma. As we take a closer look at the three concepts presented in the mural, consider the mechanics of stacking and the compounding effects of structural barriers.

Let’s work our way up by starting at the bottom. The bottom table represents Dinner Table Syndrome, a term that describes the feelings of isolation and frustration Deaf people experience during predominantly hearing and non-signing social interactions. The dinner table, often a symbol of family life and togetherness, is the hub for conversation and bonding. For hearing people, conversation involves aural and oral communication as well as subtle, nonverbal cues such as turn-taking. The impact of this for Deaf individuals in non-signing homes is a gap in communication and exclusion from these kinds of interactions. Forming the foundation of the mural, Dinner Table Syndrome represents experiences of inaccessibility for Deaf individuals raised in households where family members never learned to sign.

As Dr. David A. Meek, Deaf Studies and Deaf Education Specialist, describes:

"When I think of my family getting together for events, I often think of our gatherings during the holidays. We followed the dialogical rules in hearing conversations, everyone pretty much spoke when they had something to say, which meant that conversations between my family members often overlapped. It was often difficult for me to understand what was being said. I would often say, “What?” as I would miss what one person said because I was focusing on another person who was speaking at that moment. I did not have any technological devices (such as cellphones, portable gaming systems, laptops) that would have aided communication when I was younger. Even if those were available, I would not have been permitted to bring them to the table. We were expected to sit and eat properly and have conversations about our daily lives or what was happening in the world."

The second table, Hearing People Anxiety, denotes the mental stress experienced by Deaf people caused by inaccessibility and the historic stigmatization of language difference. This mental stress is also produced by the physical and mental exertions required by Deaf people—often in the form of lip reading and heightened focus on body language—in order to participate in social interactions typically geared toward hearing people.

The Deaf storyteller and activist Artie McWilliams describes his own struggles with anxiety:

"My anxiety is very much connected to my hearing. Every day when I step outside the front door I immediately put up a wall. I use my earphones to deflect sounds from the outside world that I wouldn’t be able to hear. The idea is if people see that I’m wearing earphones then they can’t get mad at me for not hearing something in my environment. I feel very awkward walking around without music because that means that I have to be much more alert. I feel as though I’m always being watched. If I miss something people will look at me and go, ‘Why doesn’t he respond?’ In those moments I know that I’m overthinking it. And I know that I’m being paranoid. But I can’t shut it off. I’m constantly looking over my shoulder and scanning the room that I’m in to make sure that I don’t miss anything important. And it’s really exhausting."

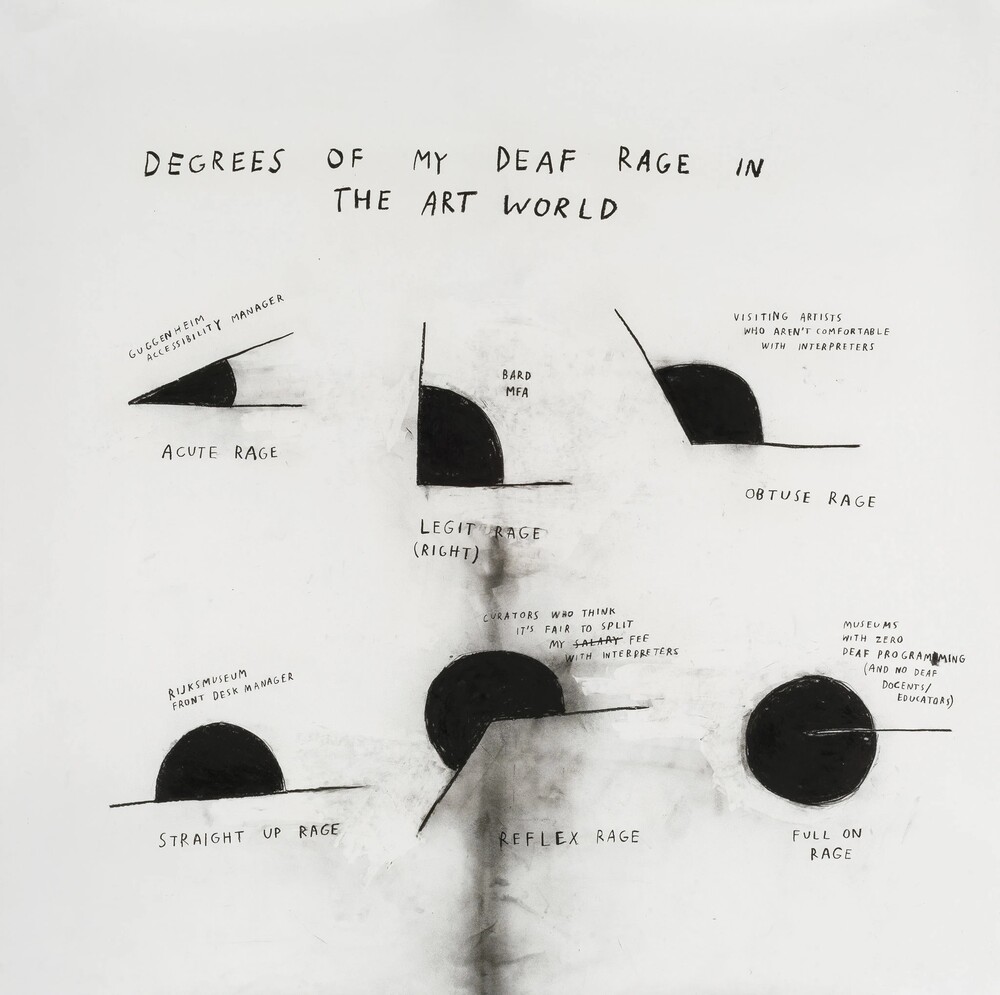

While Stacking Traumas identifies sources of trauma that impact the Deaf community, Kim's series of charcoal drawings, what she calls “Deaf Rage” drawings, identifies the frustrations she has felt navigating the art world. In Degrees of My Deaf Rage in the Art World, diagrammatic charts use the quantifiable measurements of mathematical degrees to visualize the artist’s emotional response to the lack of accessibility in museums.

Stacking Traumas also calls attention to barriers to access and equity experienced by the Deaf community in art spaces. The site-specific work functions as an intervention in the Museum, inviting us to consider the responsibility of museums and galleries, many of which lack Deaf programming and staff who are part of the Deaf community, to create a more inclusive and accessible art world.

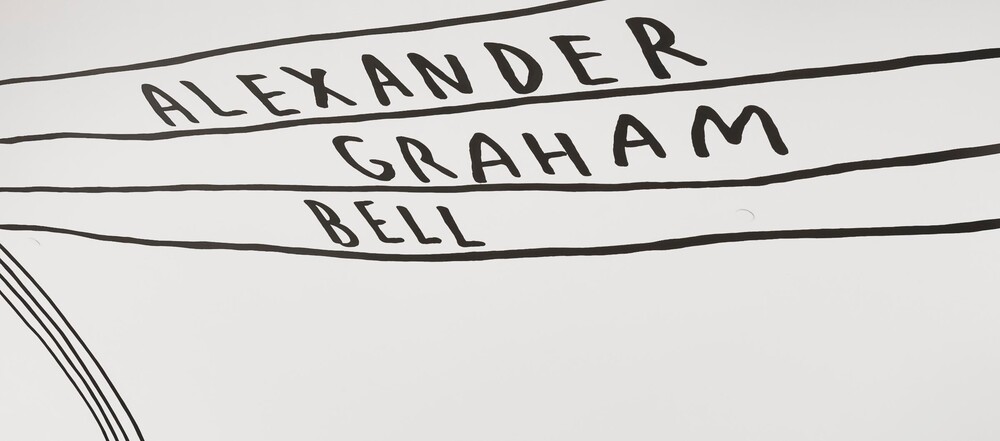

The top table in Stacking Traumas references Alexander Graham Bell (1847–1922), the inventor, scientist, and eugenicist who actively sought to suppress the teaching of sign language in Deaf education. The relationship between the top of the table and the curve of the wall, which extends into and over the visitor’s space, gives volume to a specter that continues to affect the lives of Deaf people.

Bell, who taught Deaf children in Boston during the 1870s and whose wife and mother were both Deaf, opposed teaching sign language to Deaf children. He argued for oralism, a method that teaches students to produce oral language through lip reading, speech, and mimicking mouth and breathing patterns. Bell's anti-signing campaign paralleled the growing eugenicist and nationalist movements in the United States that forced cultural and linguistic assimilation and marginalized Deaf culture; this in turn led Deaf individuals to formally and informally organize in order to create spaces of access and to advocate for Deaf rights.

American Sign Language (ASL) is at the center of the American Deaf community; however, the Deaf community and its language practices are not monolithic. There is a constant dialogue about what it means to be Deaf and what Deaf equality looks like.

Stacking Traumas explores Deaf culture through a musical lens, rejecting the conflation of silence with deafness. Kim’s monumental work uses the space of the museum to investigate sound ownership and its connection to social power, reclaiming sound and voice from the limits imposed by a hearing-dominant society and encouraging us to examine our role in how communication is constructed.

"Sound carries a lot of status. Because I was born deaf, my learning process is shaped by American Sign Language interpreters, subtitles on television, written conversations on paper, emails, and text messages." — Christine Sun Kim

Response Wall

We invite you to visit the response wall to share your response to the artwork and the issues it addresses, and to read others’ responses as well.

Further Exploration

Learn more about Christine Sun Kim and Stacking Traumas by exploring the online exhibition.

Feeling Inspired?

Now that we have spent some time with Stacking Traumas, let’s consider how our identities impact the ways in which we negotiate language and sound in different spaces.

Kim’s use of line, musical notations, and diagrams to express sound and language and its social implications is something you can do as well. Grab a piece of paper, a pen or pencil, and get creative! Using your own visual language, create a compositional drawing in response to your personal feelings of frustrations, disconnection, or anxiety during moments of communication.

Notes

“Gallery: Beautiful drawings show the music of sign language.” Ideas.Ted.Com. December 11, 2015. https://ideas.ted.com/gallery-beautiful-drawings-show-the-music-of-sign-language/ .

Holmes, Jessica A. “Expert Listening beyond the Limits of Hearing.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 70, no. 1 (2017): 171–220. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26417288 .

Howe, Blake, Stephanie Jensen-Moulton, Joseph N. Straus, Jennifer Iverson, Jessica A. Holmes, Michael B. Bakan, Andrew Dell’Antonio, and Elizabeth J. Grace. “On the Disability Aesthetics of Music.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 69, no. 2 (2016): 525–63

Kim, Christine Sun. “Navigating Laws and Accessibility in Exhibition Practices.” ArtAsiaPacific Magazine, no. 107 (March/April 2018). http://artasiapacific.com/Magazine/107/NavigatingLawsAndAccessibilityInExhibitionPractices

Kim, Christine Sun. “Sound Under New Ownership.” Negotiated Moments: Improvisation, Sound, and Subjectivity, edited by Gillian Siddall and Ellen Waterman, 187–188. Durham: Duke University Press, 2016.

McWilliams, Artie. “Deaf Anxiety.” ai-media (blog). https://blog.ai-media.tv/blog/video-lets-talk-about-deaf-anxiety .

Meek, David A. “Dinner Table Syndrome: A Phenomenological Study of Deaf Individuals’ Experiences with Inaccessible Communication.” The Qualitative Report 25, no.6 (2020): 1677–78. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol25/iss6/16/ .

Roberts, Matana. “Artwork: Christine Sun Kim.” Art Journal 76, nos. 3/4 (2017): 54–55. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45142668 .

Shoham, Natalie, Gemma Lewis, Graziella Favarato, and Claudia Cooper. “Prevalence of Anxiety Disorders and Symptoms in People with Hearing Impairment: A Systematic Review.” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 54 (2019): 649–660. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1638-3 .

All artworks are courtesy of the artist; François Ghebaly, Los Angeles; and White Space, Beijing. © Christine Sun Kim.

All installation photography is by Alise O’Brien Photography.

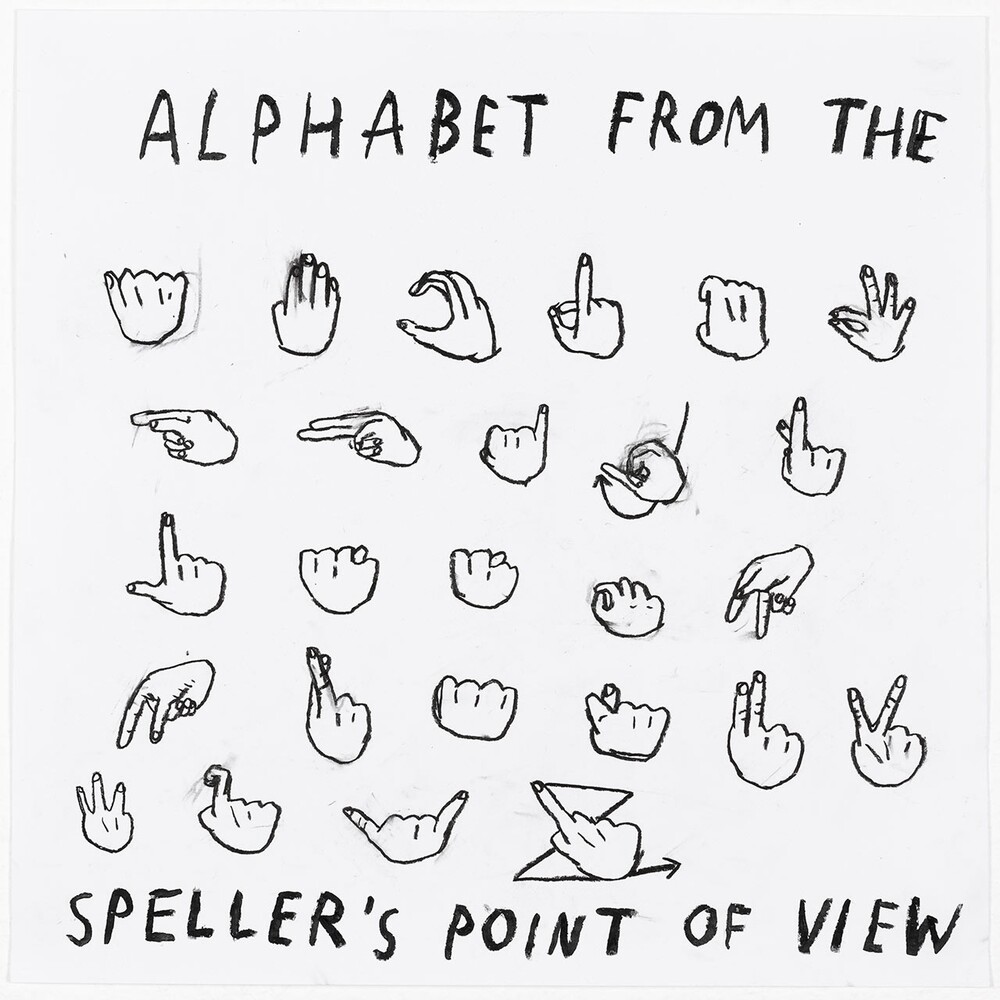

Christine Sun Kim, Alphabet From the Speller's Point of View, 2019, Charcoal and oil pastel on paper, 49 1/4 x 49 1/4".

Christine Sun Kim, Christine Sun Kim: Stacking Traumas. Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis, 2021–22.

Christine Sun Kim, Degrees of Deaf Rage In The Art World, 2018, Charcoal on paper, 49 1/4 x 49 1/4".

Christine Sun Kim, How to Tame Beamed Notes, 2015, Charcoal on paper, 11 13/16 x 14 3/4".

Christine Sun Kim, My Voice Acts Like ROYGBIV, 2015, Charcoal on paper, 11 13/16 x 14 3/4".

Christine Sun Kim, My Voice Thinks It's A Novel, 2015, Charcoal on paper, 11 13/16 x 14 3/4".

Christine Sun Kim, One Too Many Voices, 2015, Charcoal on paper, 11 13/16 x 14 3/4".

This guide was created by Alexis Carr, the spring 2021 museum education intern at the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum and a graduate student in the Department of Art History & Archaeology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

We are committed to encounters with art that inspire creative engagement, social and intellectual inquiry, and meaningful connections across disciplines, cultures, and histories. Do you have ideas or suggestions for other learning resources? Is there an artist or topic that you would like to learn more about? We would love to hear your feedback. Please direct comments or questions to Meredith Lehman, head of museum education, at lehman.meredith@wustl.edu.

.png)