Across Past, Present, and Future: Art by Black Artists

Introduction

This guide highlights a selection of artworks by Black artists in the permanent collection of the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum spanning the mid-twentieth century to today. In this guide you will encounter works of art in a range of mediums by artists who investigate ideas about identity, history, memory, and the legacy of art historical practices such as abstraction. These artworks resonate with broader dialogues about historical consciousness, the representation of Black experience, and expectations and labels assigned to artists of color by the art world.

The Rhythm of Collage

“The more I played around with visual notions as if I were improvising like a jazz musician, the more I realized what I wanted to do as a painter, and how I wanted to do it.” — Romare Bearden

Take a moment to examine this artwork, moving your eyes around the image.

Look closely at the different objects, colors, and texture.

What references to sound and time do you notice?

In this mixed-media collage a nude Black figure reclines on a sofa covered by a patchwork quilt. The juxtaposition of different materials—magazine and newspaper illustrations, fabric, and colored pieces of paper—that are cut and then reassembled come together to construct an image of a domestic space. The vibrant interior is filled with personal details, including a vase with flowers, framed pictures on the wall, a table strewn with glasses, and several small animals.

Do you notice any other figures?

After spending more than a decade as an abstract painter, Romare Bearden turned to collage as his primary mode of expression in the 1960s. For Bearden, the visual language of collage offered a way to represent a complex understanding of Black subjectivity and identity that he described as having been “collaged” by the vicissitudes of modern history. A founding member of the Harlem Artists Guild and Spiral, a collective of Black artists committed to the civil rights movement, Bearden created Black Venus during a particularly volatile year in the country’s ongoing struggle for racial justice and equity. Borrowing and mixing imagery from Western modernism and African artistic traditions, Bearden employs collage to challenge essentialist conceptions of African American cultural identity.

Do any details in this collage remind you of art objects or images you've seen before?

In Black Venus Bearden references the tradition of the odalisque—nude images of women reclining—in Western art but revises this trope to subvert white Eurocentric histories. By inserting a Black subject into the Western high-art tradition of the nude and drawing from such sources as African sculptures and masks and African American quilts, Black Venus addresses both the erasure and othering of Black bodies in the art historical canon, as well as white standards of beauty, femininity, and sexuality. As some scholars have noted, appropriating these forms can also be seen as reproducing gender tropes and objectifying strategies of the voyeuristic gaze.

Bearden’s experimentation with collage demonstrates the significant role that music played in his artistic practice. Bearden, who studied blues and jazz and often described his work in musical terms, grew up immersed in the artistic and intellectual community of Harlem near such legendary jazz and blues clubs as the Savoy Ballroom and the Apollo Theater. He was also a professional songwriter, including for Billie Holiday and Dizzy Gillespie.

In Black Venus the inclusion of a guitar player and several musical instruments as well as the overlapping arrangement of patterns, colors, and shapes allude to the improvisational techniques of jazz. Listening to jazz musicians helped Bearden in what he describes as “the transmutation of sound into colors and in the placement of objects in paintings and collages,” while also “achieving artistic structures that are personal.” Both personal and cultural, music provided visual analogies in Bearden’s complex approach to collage that mediated a Western tradition of art, contemporary culture, and the politics of the multiethnic and racially divided American society in which he lived.

“My work has developed out of a response and need to redefine the image of the man in terms of the Negro experience I know best. I felt that the Negro was becoming too much of an abstraction, rather than the reality that art can give a subject. What I’ve attempted to do is establish a world through art in which the validity of my Negro experience could live and make its logic.” — Romare Bearden

What do you think Bearden means when he says that art can give a subject reality, and why is it important?

Listen to Romare Bearden’s “Seabreeze,” originally recorded by Tito Puente and more recently by the Branford Marsalis Quartet, on the album Romare Bearden Revealed:

Deconstructing Stereotypes

What associations does this photograph bring to mind?

What details about the setting might you see if you were to zoom out?

In this 1992 lithograph by Lorna Simpson, a pair of high-heeled shoes lies on a richly textured surface. Shot from behind, the close framing and shadows focus on the backs of the heels and provide little contextual clues with which to interpret the image. If we look a little closer, we might notice that the shoes are positioned at a slight angle, as if just removed by their wearer. The shoes are also life-size, suggesting the presence of a body while also conveying its absence, an idea emphasized through the formal qualities of the photographic image that capture a physical presence of a past moment. Below the image, text reading “CURE/HEAL” provides the title of the artwork, though its relationship to the image remains open ended.

How does the text shape your interpretation of the image?

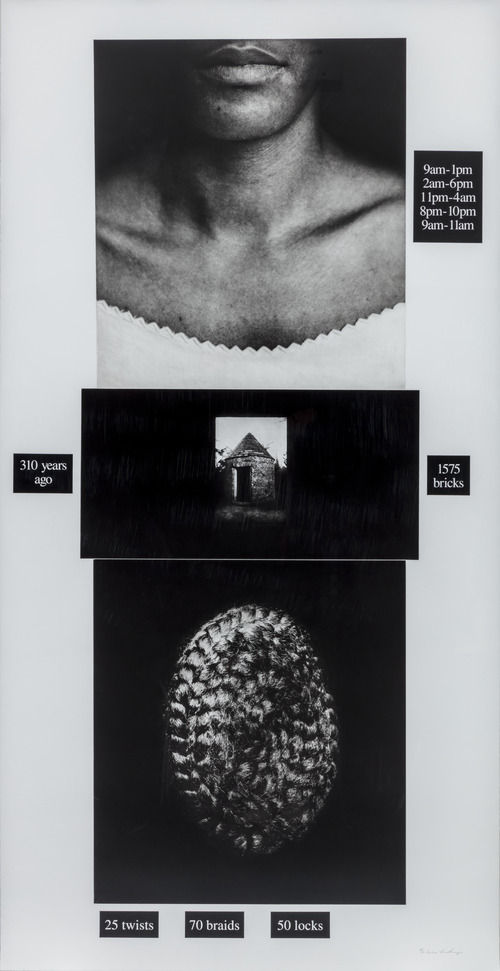

Produced as part of the collective portfolio 10: Artist as Catalyst—a project by the Alternative Museum that invited ten artists to explore social and political issues—Simpson’s contribution marks a shift in her practice in the 1990s from full-figure imagery to bodily details and gender-specific objects. Cure/Heal alludes to Simpson’s photographic images of Black women shown from the back or cropped in such a way as to deny the viewer access, challenging any attempt to identify the subject while also examining issues of visibility. Trained in documentary photography, Simpson calls attention in her work to the ways these seemingly objective images have shaped cultural memory and the representation of Black people, Indigenous people, and people of color.

In CURE/HEAL, the black-and-white image paired with text references a documentary aesthetic and photography’s one-to-one relationship with reality; however, Simpson invites us to uncover meaning through its ambiguity. To whom do the shoes belong, and what are they doing in this space? While the object is easily recognizable and socially coded as “feminine,” the withholding of further information presents us with what we can’t know about someone’s identity and experience if we rely on reductive clichés.

As Simpson describes, “I’m pointing to the fact that the wrong questions are so often asked, and this is why you don’t know anything about this person. I intentionally sought to avoid presenting a ‘them and us’ situation, them being a white audience. It is also a self description, because these stereotypes cross the boundaries of race and gender. It is not necessarily pointing a finger at any individual’s ideology, but at the language of stereotypes. Stereotypes don’t reveal anything about a woman or an experience anyway. So I am suggesting that clichés and assumptions should be discarded.”

By taking a coded marker of femininity but making the body absent, Simpson encourages viewers to see how our lives are constructed by words, images, and the social roles assigned to us. The title and its relationship with the image establish self-expression as a process of reclamation that casts off cultural stereotypes around race and gender that are both projected and internalized. The reference to healing suggests the possibility for identity to allow space for complexity, agency, and subjectivity.

Take a moment to consider assumptions and expectations people have made about your identity. What object would you choose to symbolize this in an artwork? How might you frame or title the work to reflect a process of healing?

Watch a conversation between Lorna Simpson and Thelma Golden, director and chief curator at the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York:

The Art of Silhouette

“I had a catharsis looking at early American varieties of silhouette cuttings. What I recognize, besides narrative and historicity and racism, was very physical displacement: the paradox of removing a form from a blank surface that in turn creates a black hole. I was struck by the irony of so many of my concerns being addressed: blank/black, hole/whole, shadow/substance.” — Kara Walker

Take a moment to look at these three freestanding scenes.

What do you notice about the choice of color, and what significance might it have?

The multimedia artist Kara Walker’s practice explores historical and contemporary conceptions of race, gender, and sexuality. In this set of painted stainless-steel silhouettes, three freestanding scenes depict enslaved African American women engaged in daily work: gardening, caring for a child, and cooking. The laser-cut images present viewers with flattened renderings that emphasize the outlines of the figures, exaggerating certain features but obscuring details that give a sense of individual identity. The grouping of silhouettes presents a fictional world grounded in historical events, inviting viewers to engage with our nation's past.

How does the artwork interact with the physical space?

Known for her appropriation of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century art of silhouettes, Walker recontextualizes historical images and racialized stereotypes from the antebellum South to confront the realities and legacies of institutionalized enslavement. In The Bush, Skinny, and De-boning, the silhouettes cast shadows on the wall, recalling proto-cinematic visual culture techniques, such as shadow theater and magic lantern shows, and implicating the “white wall” of the exhibition space.

In other works Walker uses life-size and mural-size silhouettes, sometimes with projectors, so that the viewer’s shadow becomes part of the artwork and contributes to its meaning. The often panoramic silhouettes of black figures displayed against a white background function as a narrative device exposing historical erasures and subverting stereotypical iconography of Black people that continues to shape present-day issues of race and whiteness in American culture.

Walker’s rise to recognition in the late 1990s was met with both praise and condemnation. Her appropriation of negative imagery and racialized caricatures stirred criticism within the art world by artists concerned that these images perpetuate racist tropes rather than deconstruct them.

These dissenting opinions, as the art historian Cherise Smith writes, “signaled a profound shift in power from the African American art establishment to the dominant (read white) art establishment...that continued to have little room for artists of color, nor, perhaps most importantly, their admission into museum collections and the art historical canon.” Artist Betye Saar, for example, has argued that Walker’s use of stereotypes is “for the amusement and the investment of the white art establishment.” The Bush, Skinny, and De-boning thus engage with broader questions related to the representation of artists of color in academia and museums.

Walker has said that the meaning of her work “is not just an examination of race relations in America today, it is a part of it, it is a part of being an African American woman artist, but it is about how do you make representations of your world given what you’ve been given.” What do The Bush, Skinny, and De-Boning communicate about the representations the world has given Walker as an African American woman artist?

Learn more about Kara Walker’s silhouette technique in this Art21 interview.

Cultural Forgetfulness and Popular Culture

What do you notice about how the skyscraper is painted?

Zoom in to take a closer look at the brushwork.

Plaza Inferno Grid presents a science fiction–like rendering of a skyscraper fragmented by a six-part grid. The blurring of paint makes the building appear as if it is burning, with flames or smoke emanating from its structure toward the sky. Six squares evoke the gridded pattern of city blocks seen from a bird’s-eye view, a compositional form that brings to mind both an urban environment and modernist geometric practices. The black background, mixed with green paint, creates a highly textured surface on the gessoed paper.

Plaza Inferno Grid is part of a 2008 series entitled Smoke that Gary Simmons created in reference to the 1972 sci-fi film Conquest of the Planet of the Apes, a cinematic metaphor for race relations in the United States. The movie, the plot of which focuses on enslaved apes revolting against human masters, was released in the years following the Watts Rebellion of 1965. The fictional world of the low-budget movie was shot in the corporate environment of Century City in Los Angeles, using its skyscrapers as the setting for a dystopian future that addresses contemporary issues of racial politics. For Simmons popular culture remains a dominant site of investigation and critique of the perpetuation of racial stereotypes, particularly how one’s formative memories are constructed through cartoons and Hollywood films. Works such as Plaza Inferno Grid are also a reminder of the ways structural racism is embedded in American cities and their design, including historical markers, monuments, and statues that map racial histories and shape public memory.

How does Plaza Inferno Grid speak to the relationship between power and place?

Simmons’s signature blurring technique adds an ambiguous quality that challenges the truth-telling of images. He first rose to prominence in the early 1990s with chalk drawings that cast critical light on racial imagery in American popular culture, including cartoons, movies, and sports. For those early works he partially erased or blurred the images to visualize cultural forgetfulness, using the material of chalk to suggest the ways information is easily altered or distorted but nonetheless leaves its mark. The blurring destabilizes the images, rendering them ghostly and ambiguous and thereby making the act of looking less passive. In doing so Simmons highlights the subjective nature of history, which is often told through the lens of the oppressor, and reminds us of the possibility for art to intervene and disrupt dominant histories.

Created and first exhibited during the 2008 presidential race, which was marked by polarities between the election of the nation’s first African American president and the coded racism of much of his opposition, Plaza Inferno Grid continues to resonate as a powerful symbol for the politics of identity and race in contemporary America.

“It’s a bittersweet thing to know that a lot of the work that I was working on 20, 25, 30 years ago is just as relevant today politically. We have the luxury of history to look back on, and we just choose not to pay attention to it.” — Gary Simmons

What does Plaza Inferno Grid say about the relationship between the past and present?

How does Plaza Inferno Grid remain relevant today?

Learn more about Gary Simmons’s erasure techniques in this interview with the artist:

Navigating the Personal and Historical

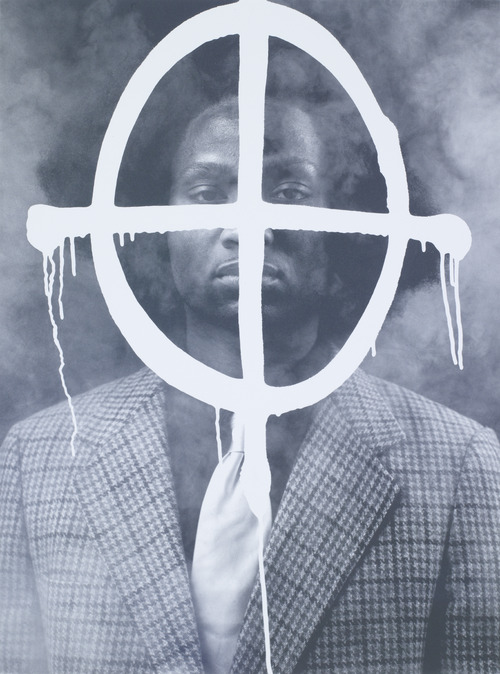

What details do you notice that might indicate who this person is and when their photograph was taken?

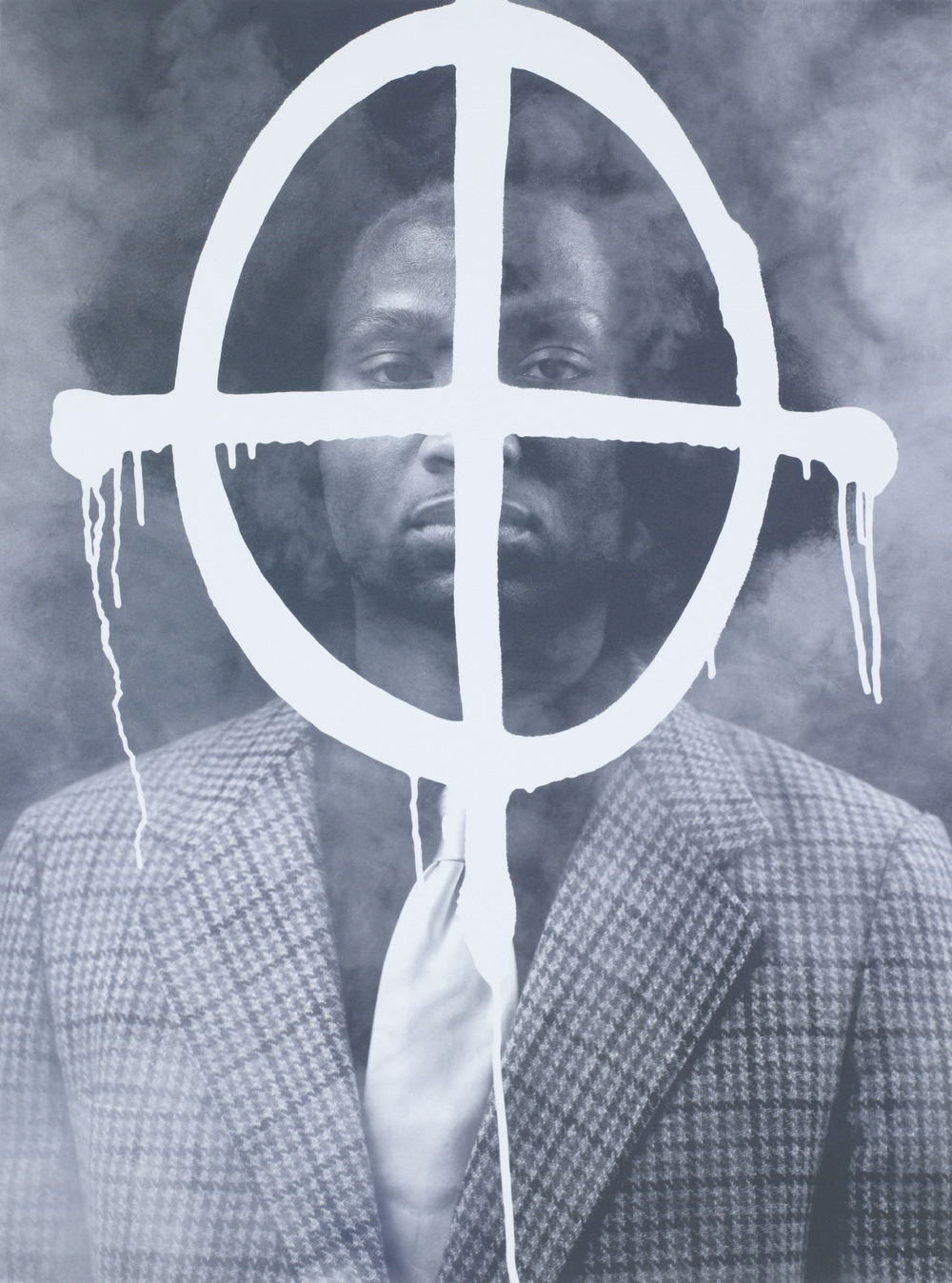

The conceptual artist and film director Rashid Johnson’s critical artistic practice engages with the history of painterly abstraction and mark-making across photography, sculpture, painting, and installation to explore the construction of identity. Johnson’s choice of commonplace materials from his childhood as well as references to Black creative and intellectual figures connect his personal and cultural identity within the larger context of Black history.

Thurgood in the Hour of Chaos presents a model dressed as Thurgood Marshall, a lawyer, civil rights activist, and the first African American Supreme Court justice, who was instrumental in the legal end of segregation in the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education (1954). The sepia-toned image recalls early photographic processes that place the reimagined portrait of Marshall within a historical context, establishing a visual link between the past and present. The overlay of graffiti-style crosshairs of a rifle scope, a recurring motif in Johnson’s work, further evokes a contemporary setting and calls attention to the distorted representation of Black Americans as threats to the state.

Inspired by the rap group Public Enemy, who used the image of crosshairs in their merchandise and album covers as a symbol of racial profiling of Black men by law enforcement, Thurgood in the Hour of Chaos suggests the ongoing targeting and policing of Black Americans as a form of legalized discrimination. The title comes from “Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos” (1988), a song by Public Enemy protesting state violence and the prison-industrial complex, which disproportionately incarcerates Black men and men of color.

Johnson has said that the generation of artists before him made work specifically about the Black experience but that his generation has had the opportunity to represent a more complex conversation around race and identity. How does Thurgood in the Hour of Chaos challenge preconceptions about racial identity?

In his work Johnson often alludes to the fantastic elements of Afrofuturism, a movement developed in the 1970s and 1980s combining history, science fiction, and non-Western theories of the origins of the universe, to address the African diaspora and historical erasures by presenting alternate futures through the lens of Black culture. Like Lorna Simpson, whose work calls for a more complex and nuanced understanding of identity that undermines monolithic notions of Black experience, Johnson’s artworks ask us to contemplate identity in relation to memory, history, present circumstances, and imagined futures.

Part of a generation of post-black artists, a term coined in the 1990s by curator Thelma Golden to characterize artists who reject the label of “Black art,” Johnson calls for an autobiographical and intersectional reading of his work as a Black man with a middle-class background rather than as a spokesperson for his race. In doing so, Johnson addresses the stereotypical portrayal of “the Black experience” in the arts, mass media, and other white institutions. By channeling Thurgood Marshall and referring to Public Enemy in Thurgood in the Hour of Chaos, Johnson articulates a shared collective history without reducing this to a singular collective experience.

“A lot of my work and a lot of my ideas have been about talking about my experience. Not every Black American’s experience is this one. That’s why the autobiographical moments in my work I feel like are almost inherently political because they tell a story that I think is often under-told about the Black character’s negotiation with this kind of intellectual engagement, with their own sense of privilege, with the battle and negotiation of living in this body.”— Rashid Johnson

Take a moment to listen to “Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos” while viewing this artwork. How does the song shape your response?

Hear Rashid Johnson speak about his artistic career and interest in materials in this Art21 video.

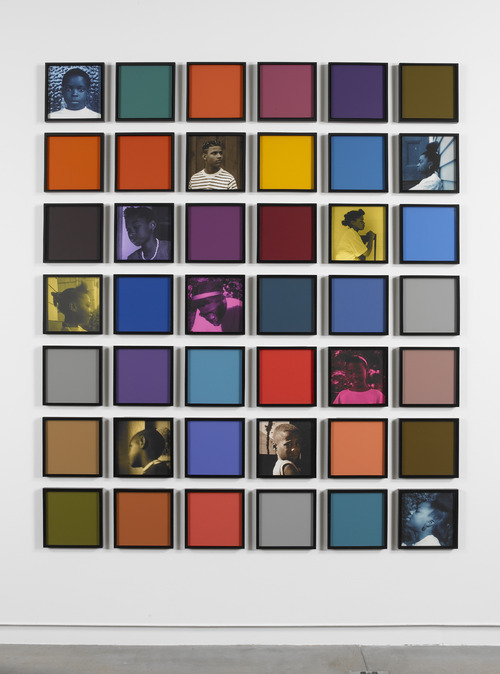

Reclaiming Color

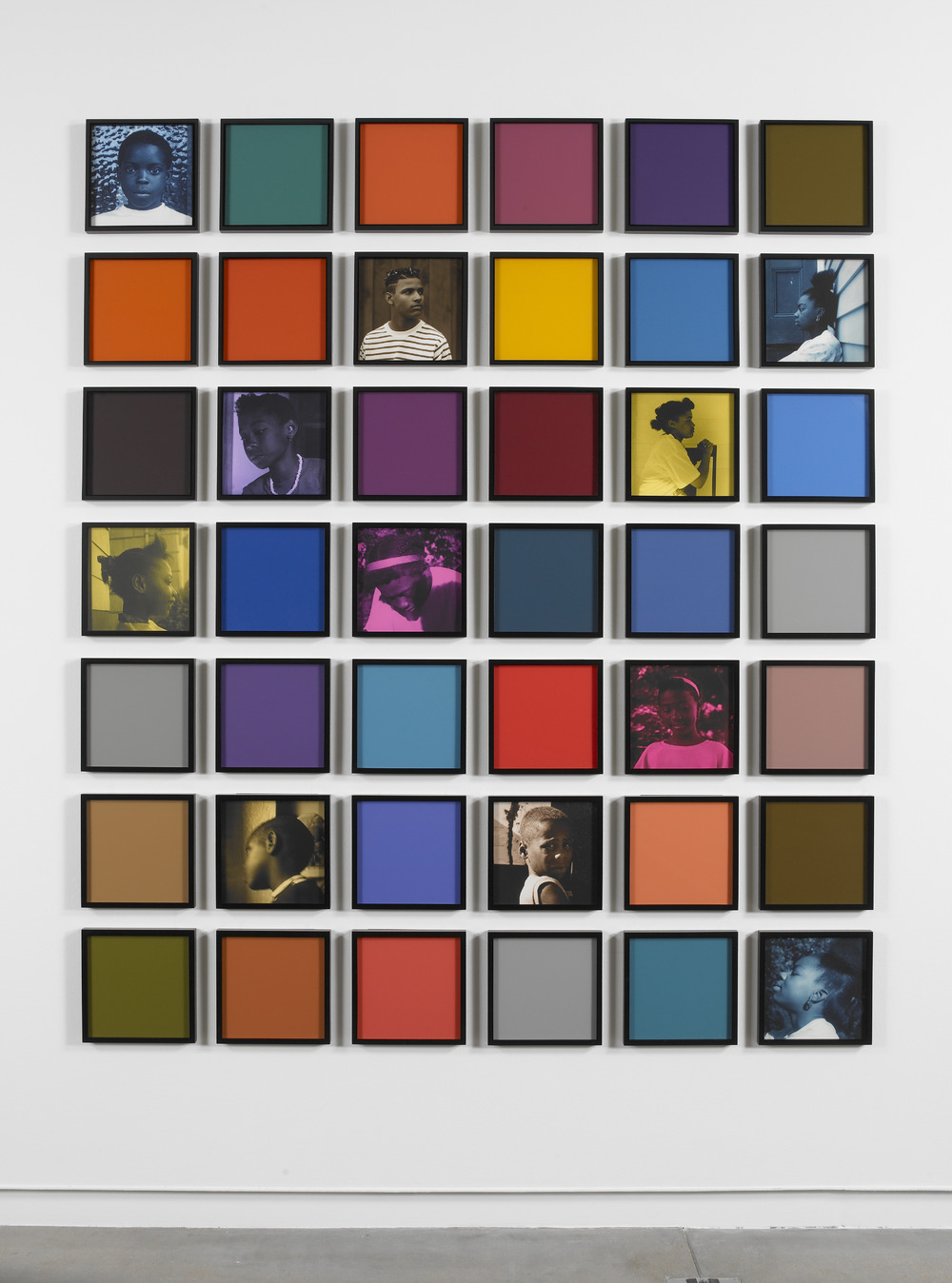

Spend some time looking at this artwork. What do you notice about the use of color and the arrangement of squares?

Are you drawn to a particular area of the work? If so, why does this stand out to you?

Untitled (Colored People Grid) consists of monochromatic square panels interspersed with photographic portraits of Black adolescents that have been overlaid with shades of magenta, yellow, burnt orange, blue, brown, and purple. The portraits highlight the individuality of the sitters through different poses, facial expressions, and orientations toward the viewer, in addition to the applied screens of color. The arrangement of these squares and the fact that, despite their differences, they are all the same size, suggest the concept of community as a collective group made up of individuals. The portraits and monochromatic panels establish a dynamic set of relations that reject any hierarchical structure and disrupt any form of categorization by color.

What is the effect of the negative space between panels? How might this composition speak to the relationship between individual and community?

Carrie Mae Weems has worked in photography and video since the 1980s, often combining text with images to explore complex histories of race, gender, and class identities in America. For Untitled (Colored People Grid), Weems reworked her earlier series titled Colored People, first created in 1989, in which she produced tinted portraits of Black youths as a means of parodying the simplistic construct of applying a color term to any human being. In this earlier series Weems investigated the term “colored” by adding labels to each group of images, such as “Blue Black Boy” and “Golden Yella Girl” to explore the range of skin colors encompassed within the term Black while also critiquing colorism, the hierarchy of social values assigned to skin tones within the Black community itself. Weems does not use text in Untitled (Colored People Grid), instead using the grid format to subvert cultural stereotypes and monolithic notions of identity and to investigate how color operates in reference to race and skin color.

The grid format of this large-scale work recalls the history of abstraction and Minimalist and Conceptualist traditions of the 1960s and 1970s, including the work of Brice Marden, who referred to the surfaces of his monochromatic paintings as “skins.” Weems complicates these practices to address issues of race and identity that were largely absent in these earlier movements. She photographs her models at an age, as she describes, “when issues of race really begin to affect you, at the point of an innocence beginning to be disrupted.” Combining both abstraction and representation, Untitled (Colored People Grid) invites multiple interpretations as a powerful statement about identity. Weems’s exploration of color expands our understanding of this and reclaims a pejorative term as a potential signifier of pride.

“My disadvantage is that for the most part when I’m viewed by the world, I am viewed only in relation to my black subject, even though I am a very complex woman working on many, many, many different levels. The first question, invariably, out of anybody’s mouth is, ‘What, is this thing about race?’ Well, it’s partly about race, but it’s considerably more. That’s the thing that interests me.” — Carrie Mae Weems

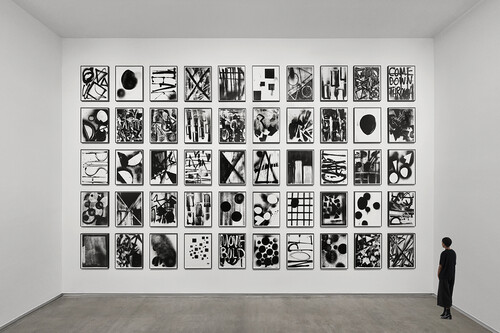

Disrupting the Canon

Take a moment to look through the artworks in this series. What kinds of artistic materials and methods do you notice?

Adam Pendleton is known for his conceptual and multidisciplinary approach to art-making, working within and across painting, screen printing, collage, video, writing, and performance. Pendleton’s practice is centered on the evolving concept of “Black Dada,” which he describes as a “way to talk about the future while talking about the past; it is our present moment.” The term is borrowed from “Black Dada Nihilismus,” a 1964 poem by Amiri Baraka (1934–2014, formerly known as Leroi Jones), and it reflects the artist’s particular interest in social resistance and avant-garde artistic movements. His work juxtaposes a variety of discourses and contexts―European modernism, the Black Arts Movement, conceptual art, experimental poetry, performance, and philosophy―in a way that interferes with our assumptions about their possible meaning, creating what the artist calls “a kind of temporary canon” or speculative history.

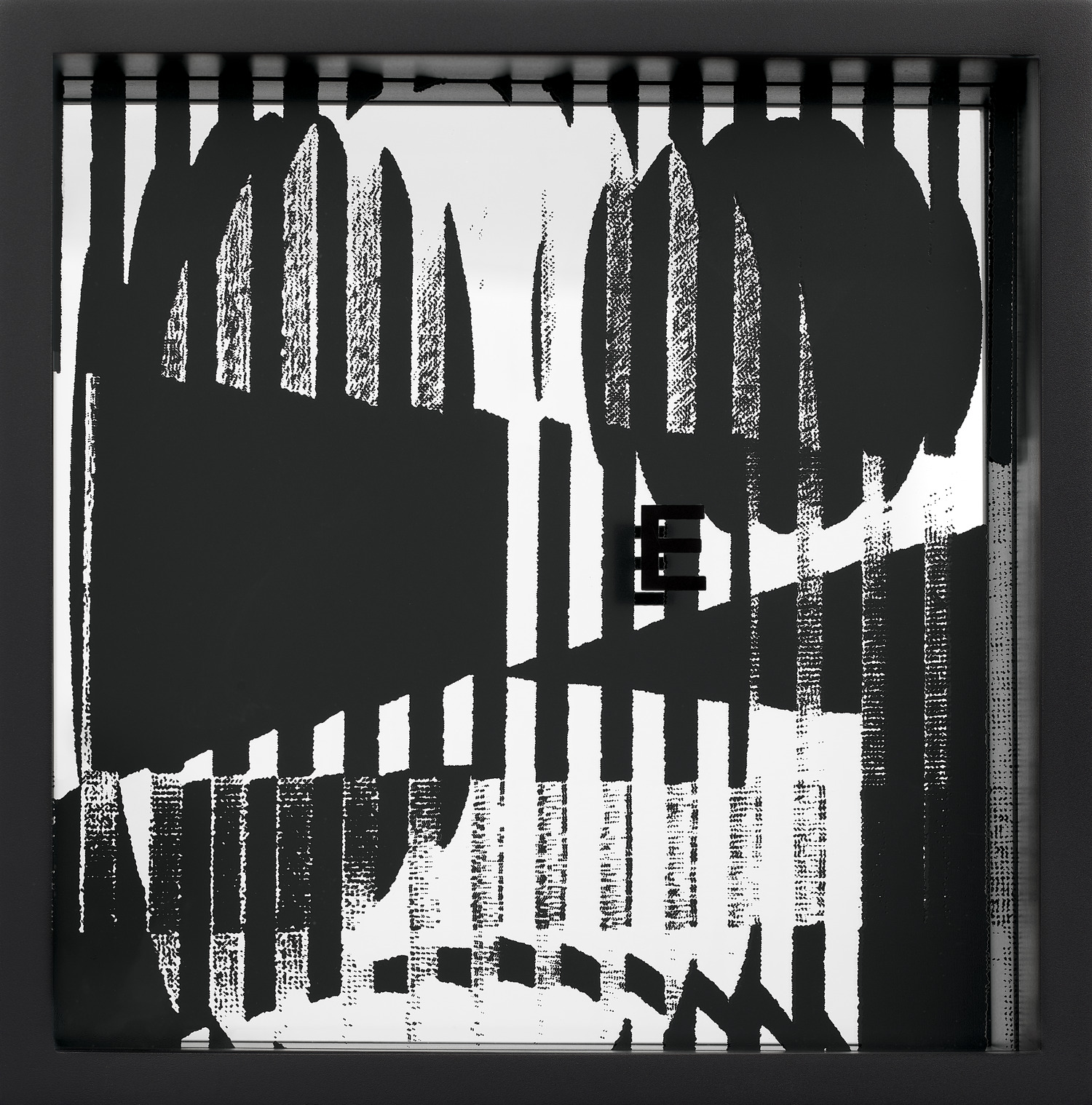

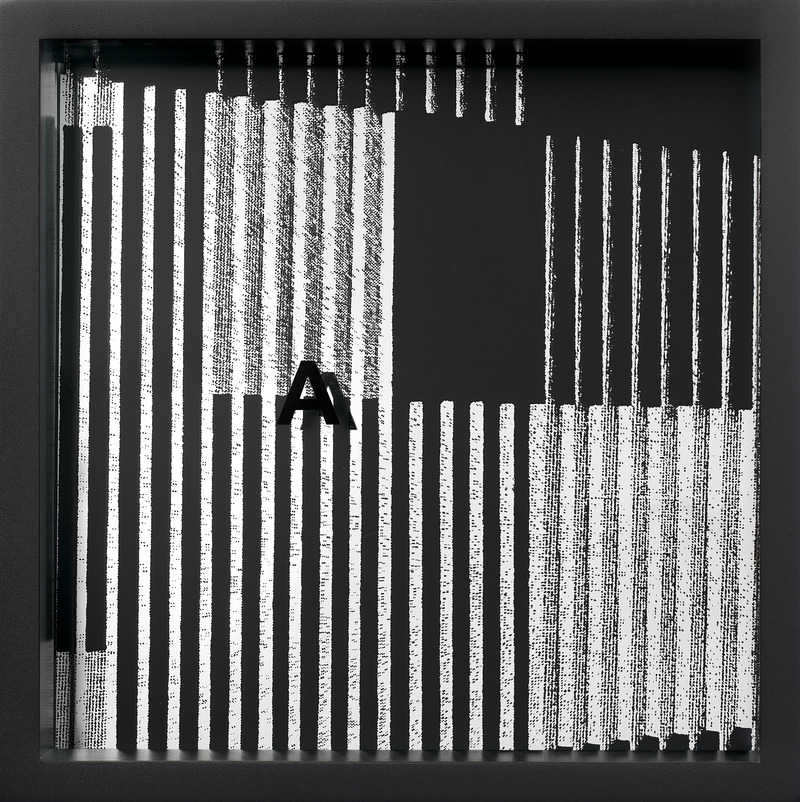

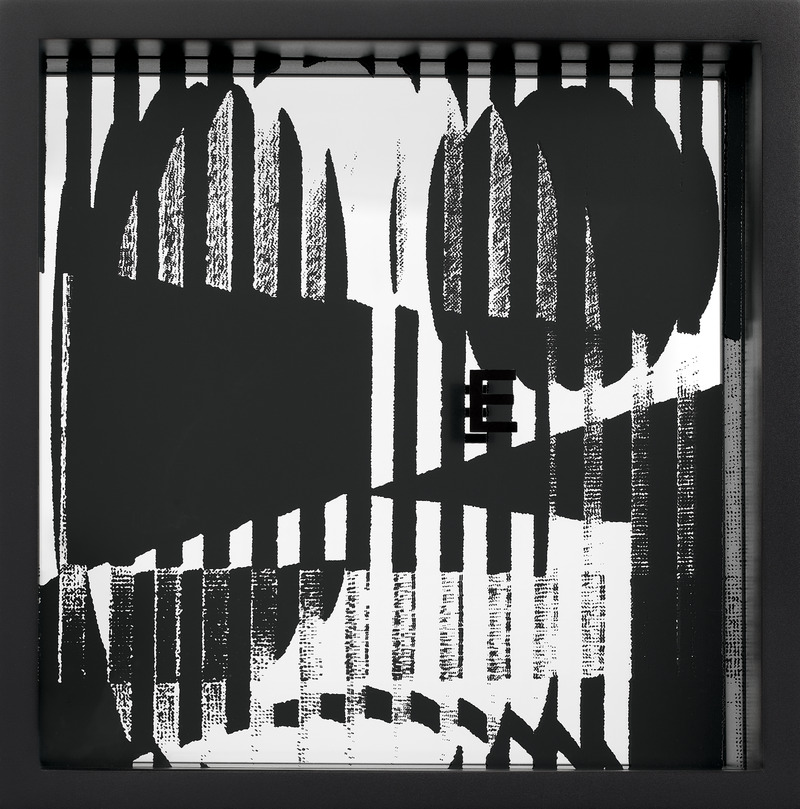

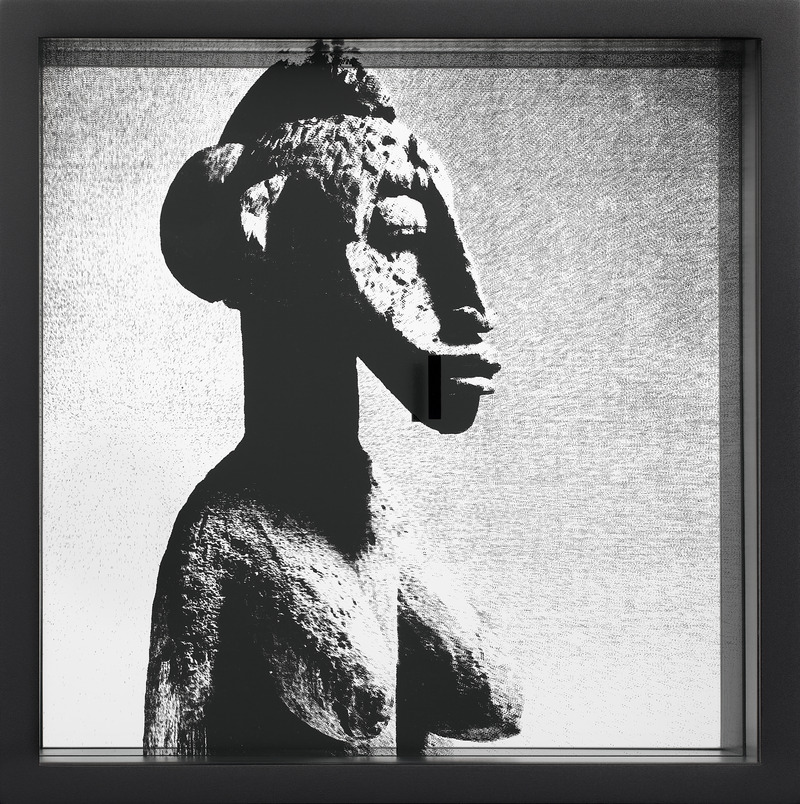

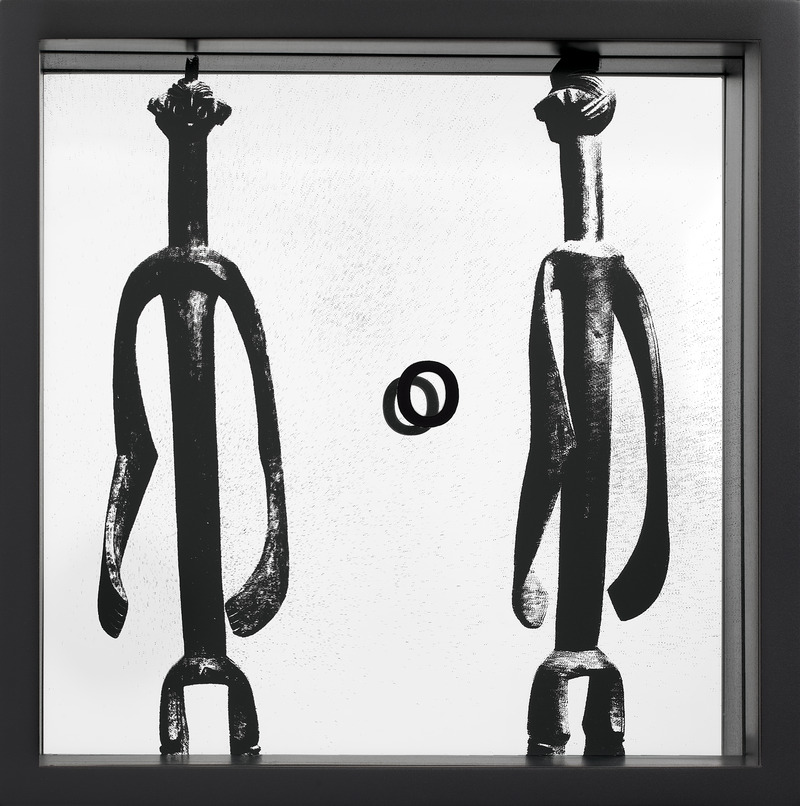

Pendleton’s System of Display series exists as an intentionally incomplete system for accumulating and arranging material from his vast personal library such that we are inclined to question what we think we know. The artist appropriates images from the pages of art publications, exhibition catalogs, historical source texts, various printed matter, and individual letters culled from poems, creating an experimental index or archive. He takes these materials and photocopies them, intentionally degrading them into high contrast black-and-white images with little contextual specificity, and then enlarges, crops, and screen prints them onto mirrored surfaces that are framed in wall-mounted black boxes.

“Increasingly, I am starting to look at the work that uses historical images as one complex image or network. I am working to establish a system of display, of organization. I want to create a situation where we’re inclined to rethink notions of the past and the future, as well as our ability to understand them enough to make reductive statements.” — Adam Pendleton

Each box is covered by a glass pane onto which is printed a single letter as indicated in the title of each work. The individual letters are taken from words in Ron Silliman’s poem "Albany" (1983). Pendleton’s use of a reflective mirror surface invites the viewer into the historical image itself, reanimating the image’s negative space with the vitality of the present moment while also serving as a reminder that meaning is contingent on relational context and is thus always fugitive.

How does Pendleton’s choice of materials invite us to engage with the artwork?

The images in System of Display, A (FATHER/Yaacov Agam, Fusion plastique, 1955) and System of Display, E (HERE/Yaacov Agam, Contrastes, 1957) come from a 1962 book on the art and writings of postwar kinetic artist Yaacov Agam. The two images of African sculpture in System of Display, I (IMPLICIT/Debles, or rhythm figure, Northern Ivory Coast, Korhogo district, Lataha village, Senufo tribe) and System of Display, O (LOOK/Ancestor figure, Eastern Nigeria, Mumuye) were taken from Elsy Leuzinger’s book The Art of Black Africa (1972). The sculptures themselves originate from the locations in their titles and are held in the collections of the Rietberg Museum, Zurich, which displays Asian, African, American, and Oceanic art, and of the well-known French collector of African art Jacques Kerchache. The images thus reference twentieth-century colonialism and the entanglements of European and African modernisms while destabilizing conventional museological practices of interpretation, categorization, and display.

The title of Pendleton’s series suggests an organized system but ultimately provides little in the way of information. What role does art play in confirming or challenging structures of organization, value, and knowledge? What similar role do museums play?

Notes

Romare Bearden

Branford Marsalis Quartet. “Seabreeze.” Romare Bearden Revealed, Clinton Studios, 2003. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aErMWtXnA_w

Carter, Richard, ed. The Art of Romare Bearden: A Resource for Teachers. National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, 2003. https://www.nga.gov/content/dam/ngaweb/Education/learning-resources/teaching-packets/pdfs/bearden-tchpk.pdf

Malone, Meredith. “Spotlight Essay: Romare Bearden.” In Spotlights: Collected by the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, edited by Sabine Eckmann, 201–4. St. Louis: Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, 2016. https://www.kemperartmuseum.wustl.edu/learn/learning-resources/bearden-romare-black-venus-1968/type/essays

Mercer, Kobena. “Romare Bearden, 1964: Collage as Kunstwollen.” In Cosmopolitan Modernisms. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005.

Rashid Johnson

Johnson, Rashid. “Rashid Johnson: ‘I Can Do This?’” Interview by The Talks. October 5, 2016. https://the-talks.com/interview/rashid-johnson/

Johnson, Rashid. “Rashid Johnson Keeps His Cool.” New York Close Up. Art 21. April 3, 2015. https://art21.org/watch/new-york-close-up/rashid-johnson-keeps-his-cool/

Public Enemy. “Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos.” It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, Island Def Jam Music Group, 1988. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZM5_6js19eM

Touré. Who’s Afraid of Post-Blackness?: What It Means to Be Black Now. New York: Atria Books, 2012.

Adam Pendleton

Pendleton, Adam. “Alex Mapes-France in Conversation with Adam Pendleton.” Adam Pendleton. New York: Phaidon Press, 2020, 19.

Gary Simmons

“Gary Simmons.” Simon Lee Gallery. 2018. https://www.simonleegallery.com/artists/gary-simmons/

Lorna Simpson

Kovach, Jodi. “Cure/Heal, from the portfolio 10: Artist as Catalyst.” In Women Artists in the Washington University Collections. Washington University in St. Louis. May 17, 2016. https://pages.wustl.edu/womenartists/articles/16920

Mercer, Kobena. “Black Art and the Burden of Representation.” Third Text 4 (1990): 61–78.

Willis, Deborah. Lorna Simpson. San Francisco: The Friends of Photography, 1992.

Kara Walker

Als, Hilton. “The Shadow Act.” The New Yorker. October 1, 2007. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2007/10/08/the-shadow-act

Perez-Villa, Angela. “Understanding Race: Kara Walker.” University of Michigan Museum of Art. March 7, 2017. https://exchange.umma.umich.edu/resources/23995/view

Smith, Cherise. “Persistent Tropes.” Art Journal 78, no. 4 (Winter 2019): 20–23.

Walker, Kara. Interview by Betye Saar. I’ll Make Me a World. Series 3, 1999, on PBS.

Walker, Kara. “Kara Walker in ‘Stories.’” Art 21. September 9, 2003. https://art21.org/watch/art-in-the-twenty-first-century/s2/kara-walker-in-stories-segment/

Carrie Mae Weems

Unruh, Allison. “Spotlight Essay: Carrie Mae Weems.” In Spotlights: Collected by the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, edited by Sabine Eckmann, 258–61. St. Louis: Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, 2016. https://www.kemperartmuseum.wustl.edu/learn/learning-resources/weems-carrie-mae-untitled-colored-people-grid-200910/type/essays

Weems, Carrie Mae. Quoted in Ann Temkin, ed., Color Chart: Reinventing Color, 1950 to Today. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2008.

Romare Bearden (American, 1911–1988), Black Venus, 1968. Mixed-media collage, 29 3/4 x 40 3/16". University purchase, Charles H. Yalem Art Fund, 1994. © Romare Bearden Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960), Cure/Heal, from the portfolio 10: Artist as Catalyst, 1992. Lithograph, 53/100, 26 x 26". University purchase, 1994.

Kara Walker (American, b. 1969), The Bush, Skinny, and De-boning, from Edition No. 19, 2002. Painted stainless steel in 3 parts, 29/100, 5 3/4 x 5 1/2 x 3/4"; 4 1/2 x 4 1/8 x 3/4”; and 5 3/4 x 6 x 3/4”. Gift of Peter Norton, 2015.

Gary Simmons (American, b. 1964), Plaza Inferno Grid, 2008. Oil and pigment on 6 pieces of gessoed paper, 102 x 67 1/2 x 1/2" (overall). University purchase, Bixby Fund, 2012.

Rashid Johnson (American, b. 1977), Thurgood in the Hour of Chaos, from the portfolio America America, 2009. Photolithograph, 47/50, 29 5/8 x 22". Gift of Exit Art, 2013.

Carrie Mae Weems (American, b. 1953 ), Untitled (Colored People Grid), 2009–10. 31 screen-printed papers and 11 inkjet prints, AP 2/2 (ed.5), 87 7/8 x 75 3/16" (overall). University purchase, Bixby Fund, and with funds from Bunny and Charles Burson, Helen Kornblum, Kim and Bruce Olson, and Barbara Eagleton, 2014.

Adam Pendleton (American, b. 1984), System of Display, A (FATHER/Yaacov Agam, Fusion plastique, 1955), 2018–19. Screen prints on acrylic and mirror, 9 13/16 × 9 13/16 × 3 1/8". University purchase, Bixby Fund, 2019.

System of Display, E (HERE/Yaacov Agam, Contrastes, 1957), 2018–19. Screen prints on acrylic and mirror, 9 13/16 × 9 13/16 × 3 1/8". University purchase, Bixby Fund, 2019.

System of Display, I (IMPLICIT/Debles, or rhythm figure, Northern Ivory Coast, Korhogo district, Lataha village, Senufo tribe), 2018–19. Screen prints on acrylic and mirror, 9 13/16 × 9 13/16 × 3 1/8". University purchase, Bixby Fund, 2019.

System of Display, O (LOOK/Ancestor figure, Eastern Nigeria, Mumuye), 2018–19. Screen prints on acrylic and mirror, 9 13/16 × 9 13/16 × 3 1/8". University purchase, Bixby Fund, 2019.

All artworks are copyright the artist or the artist’s estate unless otherwise specified. Images on this tour are for educational purposes only and are not licensed for commercial applications of any kind.

We are committed to encounters with art that inspire creative engagement, social and intellectual inquiry, and meaningful connections across disciplines, cultures, and histories. Do you have ideas or suggestions for other learning resources? Is there an artist or topic that you would like to learn more about? We would love to hear your feedback. Please direct comments or questions to Meredith Lehman, head of museum education, at lehman.meredith@wustl.edu.

.png)