Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Colored People Grid), 2009–10

Allison Unruh

Associate Curator, Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum

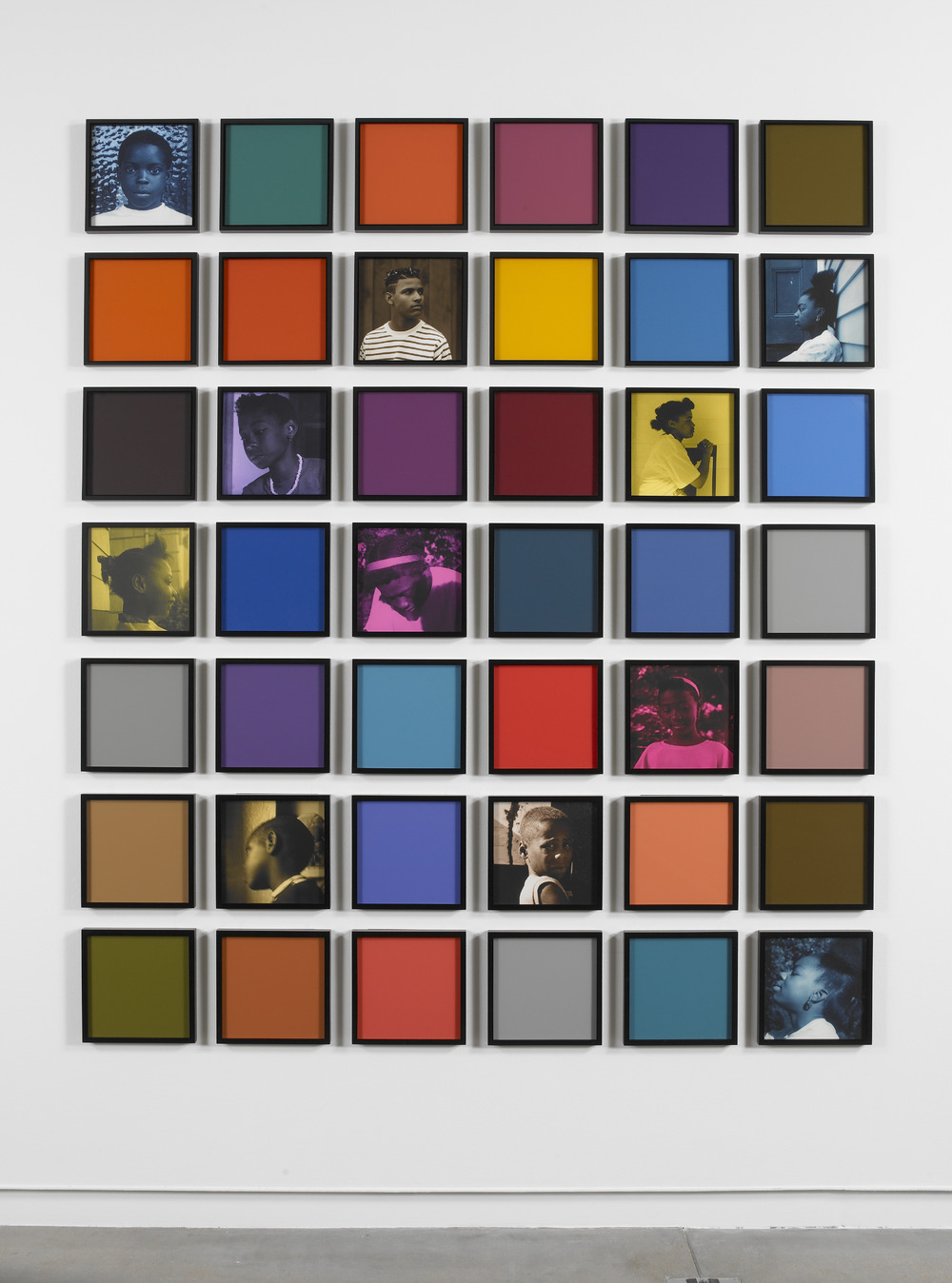

Over the past four decades Carrie Mae Weems’s artistic practice has centered on the use of photography to explore issues of race, the body, and the power structures that shape the way we understand the world.1 Her work often engages multilayered and poetic visual strategies to subvert cultural stereotypes, destabilizing monolithic notions of identity to embrace more complicated ways of seeing and thinking. Weems’s Untitled (Colored People Grid) presents the viewer with a large-scale grid that brings together eleven photographic portraits of African American adolescents arrayed in an irregular sequence among thirty-one multihued monochromatic panels. The photographs, drawn from Weems’s Colored People series (1987–90), portray introspective adolescent boys and girls at an age, as Weems put it, “when issues of race really begin to affect you, at the point of an innocence beginning to be disrupted.”2 Thus, in Untitled (Colored People Grid), Weems initiates a dialogue with her own oeuvre, in particular a series whose title, which contains a term commonly used to refer to non-Caucasians from the nineteenth century until around 1960, makes direct reference to race.3 Employing the grid, the monochrome, and photographic portraiture, she points to ways in which color has operated in reference to race in various social and historical contexts while also suggesting more expansive ways to think about color.

In her choice of the gridded format, Weems inserts herself into a legacy of artists who have engaged with this basic structure since the early twentieth century.4 As a system based on serial repetition, the modernist grid in artistic practice can be understood as self-referential and autonomous; at the same time it informs the basic structure of the modern world, from systems of technology to the built environment. Weems’s use of the grid underscores the nonhierarchical qualities of this form, as each unit possesses the same dimensions, and whether a portrait or a monochromatic panel—whether representational or abstract—each panel is identically framed and given equal visual weight. The rejection of any clear hierarchical structure also plays out in the arrangement of the panels, as there is no discernible compositional privileging of one part of the work over another. In place of symmetry and balance, there is a dynamic visual play in the alternation of images and monochromatic panels in unpredictable intervals. The critique of systems of power plays a recurring role in Weems’s work. In this light we can see the grid here as illuminating democratic overtones through its foregrounding of antihierarchical systems.5

In addition to the way Untitled (Colored People Grid) can be seen as displacing hierarchical logic, the work’s formal elements also emphasize relational dynamics. This is particularly foregrounded by Weems’s use of color in the composition. The colored panels, the tones of which range from bright to muted, each with an even and unmodulated surface, project forcefully from a distance and then present an optical overload when viewed up close. These panels are made from Color-aid paper, an industrially fabricated material that was initially developed in 1948 for photography studio backdrops. Within the gridded format, Weems’s use of commercially produced hues also evokes the notion of color charts, through which colors are standardized for easy consumption. Given the seemingly unstructured relation of panels, however, the idea of standardization itself appears to be displaced, even parodied through the strangely individualized randomness of the relationship between the monochromes and the black-and-white photographs, which are each tinted in a different hue. In some cases the colors of the photographs correspond to the adjoining monochromatic panels, while in others they contrast. The result is a rich array of chromatic interactions that encourage the active movement of the viewer’s eye across the surface of the work.

Weems’s play with color on a formal level is also inextricably connected to ideas of difference and multiplicity and the social and political implications of color. While the African American youths shown in the photographs might be designated “black” today, the artist presents their portraits in the context of an adamantly diverse spectrum of color, through both the tinting of the photos and the surrounding field of monochromes. The application of the overlaid hues to the photos suggests a colored lens through which we see each image. “I started toning them in all those different colors,” Weems has explained, “in the hopes of stretching the conversation beyond the narrow confines of race as we know it in the United States, starting to play out a much brighter idea about both the sort of absurdity of color and also [its] beauty and poignancy.”6 Weems’s work can be understood as aesthetically disrupting and displacing any form of categorization by skin color, in part through the broad scope of colors and also through the potential of the grid’s units to expand infinitely, underscoring concepts of multiplicity and diversity. Although we can read such meanings through the formal operations of the work, the title also interjects historical associations into the frame, evoking the troubled history of racism in the United States and segregation based on skin color. Yet through the contextualization of this phrase in the formal language of Weems’s work, we can see it being appropriated from this racially charged context in order to take on more open-ended meanings.

In the context of the colorful grid, the tinted portrait photos operate in a different way than they did in the earlier Colored People series. In the earlier series the photographs are presented singly or in triplicate, captioned with phrases used by African Americans to describe variations of “black” skin tones: “Magenta Colored Girl,” “Blue Black Boy,” and so on. These words are printed in capital letters below a photo that is toned with the corresponding color. Having a poetic and melodic quality when read sequentially, the phrases can also be seen to critique hierarchies of color within the African American community, such as privileging lighter skin over darker skin in parallel with white hierarchies.7 Weems’s application of these skin-tone labels was inspired by her own experience of being called a “red bone” girl when she was a child; she then explored the idea of turning around a potentially derisive nickname to see it instead in positive terms.8 The variety of colors and the pairing of tinted photos and labels ultimately resist both the simplistic labeling of “colored” and the systems of categorization applied to the African American community, by African Americans themselves as well as by white Americans. In addition, each of the eleven portraits conveys a sense of insistent individuality through close-up framing and attention to subtle differences of mood and appearance, casting them in sharp contrast to the simplifying labels. In Untitled (Colored People Grid), however, Weems has freed the portraits from those labels, so that they read primarily in a relational manner across the space of the grid. With their subjects looking directly out, up, or away from the camera, the portraits amplify the dynamics of difference and relationality, celebrating variety and individuality within a social group—African American youths—that has so often been stereotyped in American culture. In this way, by recontextualizing photographs from the earlier series within a modernist grid, Weems opens up a set of associations that take race as a point of departure for an exploration of larger issues of humanity, in this case, the complexity of color and its meanings.

- 1 For a comprehensive overview of Weems’s career, see Kathryn E. Delmez, ed., Carrie Mae Weems: Three Decades of Photography and Video (Nashville: Frist Center for the Visual Arts; New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012).

- 2 Carrie Mae Weems, quoted in Ann Temkin, ed., Color Chart: Reinventing Color, 1950 to Today (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2008), 184.

- 3 For an account of the complexities surrounding the term colored, see Henry Louis Gates, Colored People: A Memoir (New York: Knopf, 1994).

- 4 For more on the aesthetics of the grid, see Rosalind Krauss’s seminal essay “Grids,” October 9 (Summer 1979): 50–64, and Sabine Eckmann and Lutz Koepnick, [Grid<>Matrix] (St. Louis: Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, 2006).

- 5 This can be understood, in part, as a response to the context for which she originally developed this work. The first iteration of this composition was commissioned by the Foundation for Art and Preservation in Embassies (FAPE) program as a site-specific installation in the lobby of the US Mission to the United Nations in New York City. In this context it announces “the breadth of our country’s multifaceted culture to a larger global community.” Kathryn E. Delmez, commentary on Colored People and Untitled (Colored People Grid), in Delmez, Carrie Mae Weems, 70. For more on FAPE, see www.fapeglobal.org. The version in the Kemper Art Museum is AP 2/2 (ed. 5); there are slight variations in the monochromatic panels between it and the version commissioned by FAPE.

- 6 Carrie Mae Weems, quoted in an audio guide by the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, www.albrightknox.org/collection/collection-highlights/piece:weems-colore....

- 7 See Delmez, commentary on Colored People and Untitled (Colored People Grid), 70. See also Andrea Kirsh, “Carrie Mae Weems: Issues in Black, White and Color,” in Carrie Mae Weems, ed. Andrea Kirsh and Susan Fisher Sterling (Washington, DC: National Museum of Women in the Arts, 1993), 16.

- 8 “When I was a kid, I was called ‘red bone,’ so that idea of being a red girl as opposed to a caramel color girl or a chocolate color girl, I thought was really sort of fabulous, in a way of really being very specific about what someone looked like, what their color reflected.” Weems, audio guide, Albright-Knox Art Gallery.