19th- and Early 20th-Century American and European Art

Introduction

This guide explores highlights from the Gertrude Bernoudy Gallery of the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum. In this learning resource you will move through the four rooms of the gallery, chronologically from the nineteenth to the twentieth century, encountering artworks that invite us to consider how artists responded to the world around them.

The Changing Cultural and Social Landscape

Let’s begin with two landscape paintings by artists who responded to the social and cultural conditions of the nineteenth century through different approaches.

Spend some time looking at this painting, allowing your eyes to wander around the canvas.

In this painting sweeping ruins start on the left with a thirteenth-century watchtower anchoring the composition and recede to the far right with a Roman aqueduct, a feat of engineering that could transport water long distances, here depicted in various states of decay. The crumbling ruins are set within a pastoral scene of a diminutive shepherd with a dog and herd of goats, seemingly unaware of their architectural surroundings. In the foreground, a skull rests in a flowing stream symbolizing the passing of time as well as historical and natural cycles of destruction. Human history appears on the verge of disappearing while nature continues in its wake. Yet the presence of the past remains even if in a ruined state, suggesting the possibility for modern civilization to stand the test of time.

Considered a founding figure of the Hudson River school, a mid-nineteenth-century group of American landscape painters, Thomas Cole aimed to elevate landscape painting to an intellectual pursuit, or what he called “a higher style of landscape,” through its potential to convey moralistic narratives. Based on sketches of the Claudian Aqueduct that Cole made while traveling in Italy, Aqueduct near Rome (1832) shows the artist’s skillful attention to topographical details and architectural subjects. The remnants of the past and looming shadow suggest the rise and fall of civilizations, a theme that Cole would continue to explore in his series The Course of Empire (1833–36) and one that would serve as a cautionary reminder to a young American audience with imperialist ambitions.

The images of ancient ruins also speak to the British-born artist’s awareness of trends in the European art market and his ability to bring them to a wider transatlantic public. Cole was influential in the development of an American style of painting that adapted European romantic and sublime traditions to celebrate the American landscape as a marker of national identity.

Cole turned to the ancient past to caution a contemporary audience about the fragility of human endeavors during a period of nation building and settler colonialism. What does this artwork have to say to a twenty-first-century audience?

Take a moment to notice the colors and brushwork in this painting. Imagine walking through this landscape. What sounds, smells, and textures come to mind?

In this wooded scene, intertwined branches and leaves create a shaded canopy that frames a clearing illuminated by sunlight and blue sky. The play of light and color and thick layering of paint immerse the viewer in the dense foliage, evoking a sensorially-rich experience of walking through a concealed and unspoiled forest, untouched by signs of industrialization.

A prominent figure of the French Barbizon school, a group of artists who painted around the Forest of Fontainebleau and who were known for working en plein air (out of doors), Narcisse Virgile Diaz de la Peña received praise from critics at the 1847 Salon exhibition for his unmediated representation of nature. Plein air painting of the French countryside seemingly offered an intimate connection with nature no longer possible in urban environments. The varied paint application, visible brushstrokes, and lack of fine detail in Wood Interior (1867) simulates this direct experience of nature, suggesting a spontaneous execution necessitated by working outside the studio.

The bucolic setting of Fontainebleau, located roughly thirty miles southeast of the French capital and historically home to French rulers, became a popular tourist destination for the middle class looking to escape the artificiality of modern life. Travel to the countryside was made possible through the newly established national railway, an industrialized mode of transportation that would shape the perception of time, space, and distance. By the second half of the nineteenth century, Fontainebleau was overrun with signs of industry and tourism, something that Diaz de la Peña’s painting purposefully omits.

Where do you go to find escape from the flow of everyday life?

Up Next: Cole’s and Diaz de la Peña’s paintings give insight into the cultural and social landscape of the mid-nineteenth century, addressing concerns around cultural and national identity and industrialization in different contexts. We now turn to artworks from the late nineteenth century that were inspired by people and scenes drawn from contemporary life.

Representing Contemporary Life

The second room of the Bernoudy Gallery explores Realism, a term coined by French art critic and novelist Jules François Félix Fleury-Husson, who wrote under the name Champfleury, in the 1840s to describe art that represented subjects drawn from contemporary life and the physical world with precision and empathy. The shift away from the idealized treatment of subjects that had dominated Western art until this point coincides with the social and political upheavals of the nineteenth century, marked by revolutions, industrialization, scientific advancements, and democratic reform.

We will now turn to two artworks to further explore realist subject matter and its connections to the shifting cultural and sociopolitical context at the end of the nineteenth century.

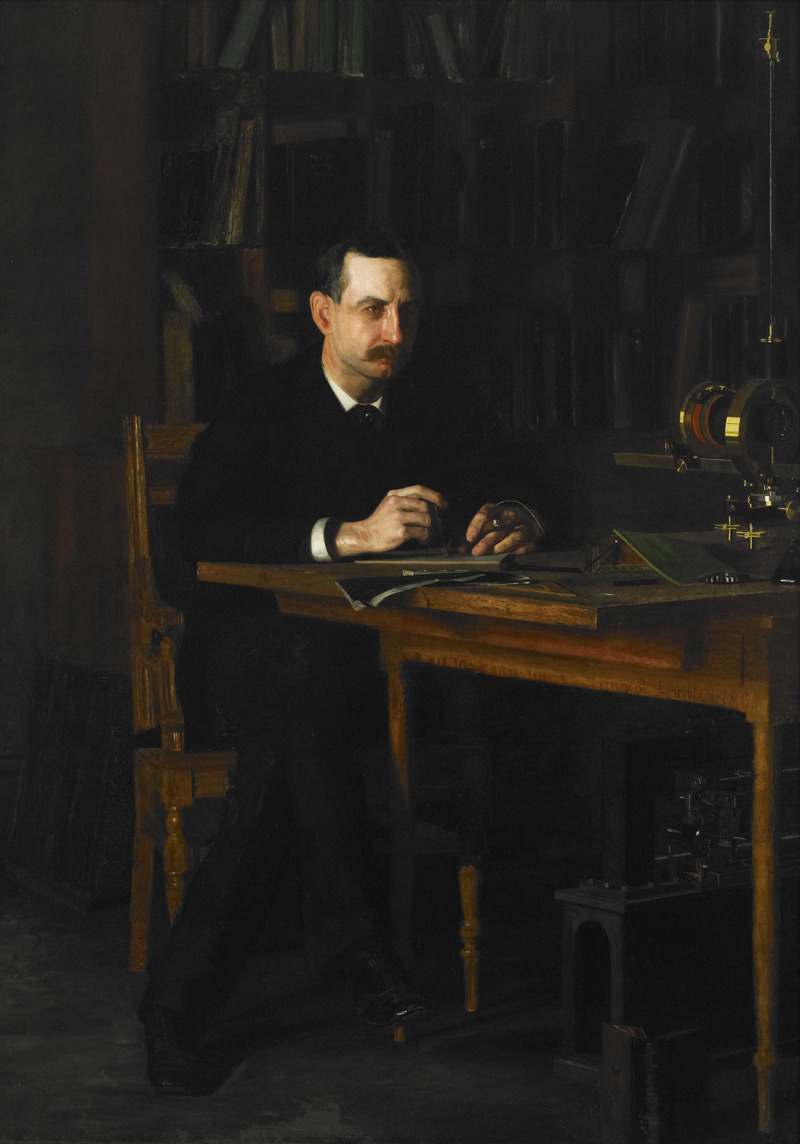

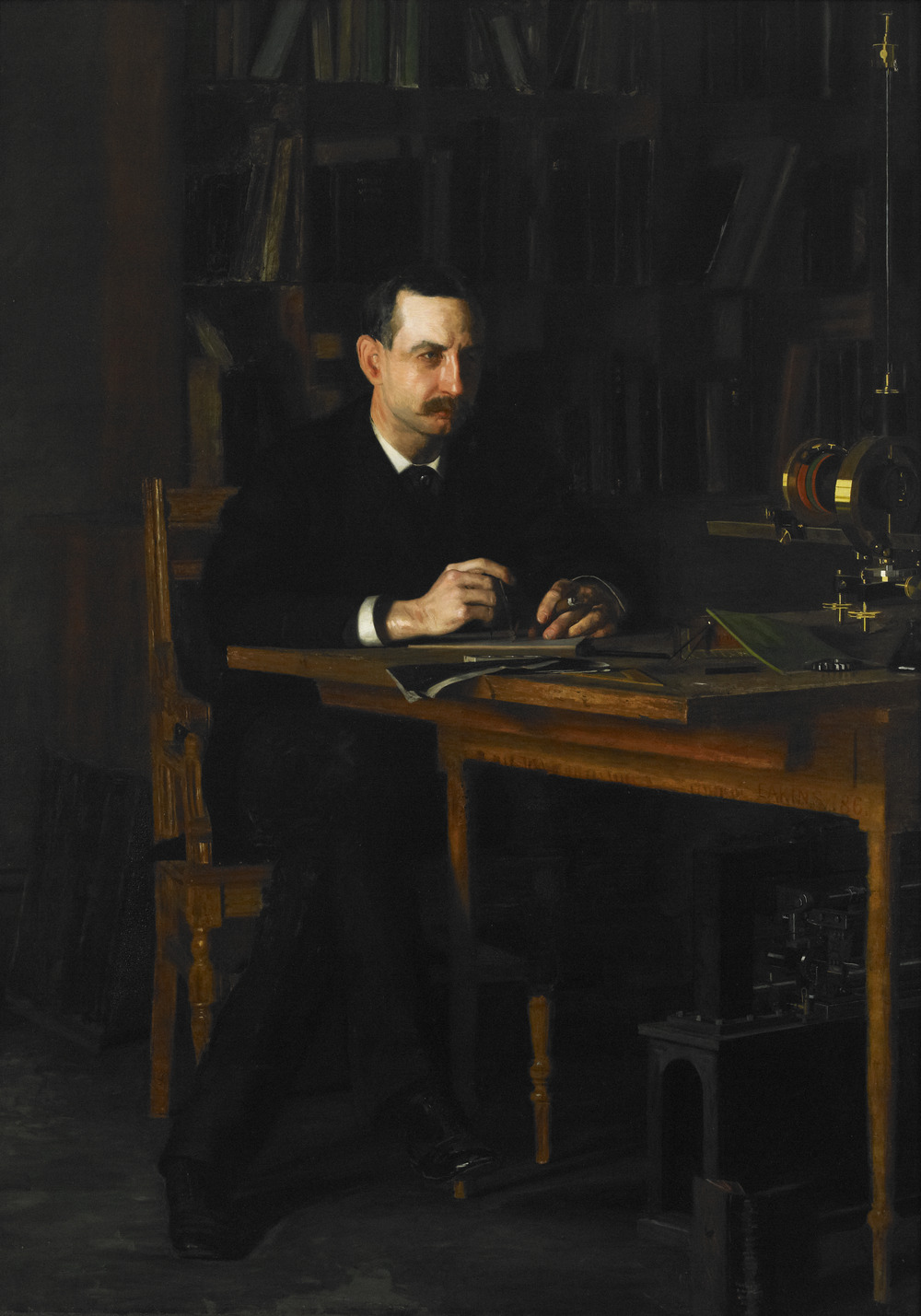

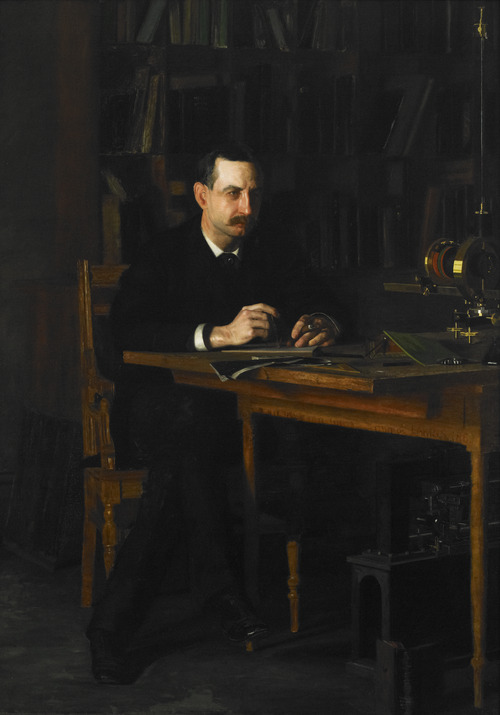

Take a moment to observe this portrait, keeping in mind any objects or details you notice.

What might the sitter’s body language and the setting for their portrait tell us about this person?

American artist and proponent of Realism Thomas Eakins often painted portraits of friends who were accomplished in the fields of science, medicine, and academia. In this 1886 portrait of William Denis Marks, a St. Louis native and distinguished professor of dynamical engineering at the University of Pennsylvania, the dark and indistinct background draws our attention to the sitter who appears lost in thought, seated at his desk with a cigar and measuring tool in hand and surrounded by books and various tools. Below and on top of the desk rest two large and complex instruments that point to the sitter’s professional identity. The light shining on Marks’s head, hands, and the machine on his desk creates a visual link between the figure’s thoughts and his experiments.

This portrait brings together the artist’s and sitter’s shared interest in photography, a relatively recent technology first publicized in 1839 that blurred distinctions between art and science. Marks was influential in the development of motion photography, which the artist alludes to by depicting him across from the chronograph, a machine Marks invented to capture movement unobservable through sight alone and one that Eakins would use in an 1884 study at the University of Pennsylvania to investigate motion with photographer Eadweard Muybridge.

The chronograph references Marks’s achievements in the field of engineering as well as the capacity for technology and science to advance realism in painting through direct observation. In addition to his studies on motion, Eakins used photography as a tool to render his subjects with more precision, projecting images onto his canvases to help draw the outlines of forms before applying paint. Eakins used this technique to produce the detailed rendering of the chronograph we see in this artwork. The textured brushwork on the figure, however, contrasts with the precise treatment of the machine, showing Eakins’s mastery of different painterly techniques and perhaps asserting the flexibility of painting as a medium in contrast to emerging modes of photomechanical reproduction.

If you were going to have your portrait made, what objects would you pose with to communicate something about yourself?

Take a moment to observe the body language of the figures in this painting. How do the figures relate to each other and to the space?

What mood does this artwork bring to mind?

Spanish artist Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida based this 1892 composition on an incident he witnessed on a third-class railway carriage between Madrid and Valencia, where a female prisoner was being transported by civil guards. In this large painting, a prisoner sits in isolation on a train, watched over by two officers who accompany her. The bright sunlight highlights the woman’s face as her downcast gaze draws attention to her bound hands tucked inside the dark clothing that seems to engulf her body. The emptiness of the space and expression of defeat conveyed through the prisoner’s body language, and echoed in the guards seated behind her, increase the sense of solitude and misery.

The title of the painting includes the name Margarita, perhaps referring to a slang term for sex workers in Valencia at the time. The name also suggests a literary connection to Goethe’s tragic play Faust (1829), in which Margaret (also called Gretchen) commits infanticide after being deceived by the protagonist Faust and is then punished by society for her crime. The literary allusion, something a nineteenth-century audience would have been aware of, leaves the viewer to speculate about the events surrounding the figure’s imprisonment. The painting gained much international attention and solidified Sorolla’s reputation in the United States, earning a Medal of Honor at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893.

To recreate this scene with meticulous detail, Sorolla painted models in an actual railway car rather than in a studio. The detailed rendering of subject drawn from a firsthand account speaks to the artist’s realist aesthetics. Yet the staging of this moment and the adjustments Sorolla made, such as the absence of other passengers and what appear to be shrunken windows, reveal the theatricality of what is represented and invite us to engage more empathetically with the prisoner’s experience.

How does Sorolla’s staging of a real-life scene contribute to our empathetic response?

What might the literary reference in ¡Otra Margarita! say about the status of women in nineteenth-century Spain?

Up Next: Both Eakins and Sorolla chose subjects from their surroundings to represent contemporary life, embracing the realist credo that an artist must be de son temps (of their time). We now turn to artworks at the turn of the twentieth century by international artists whose work was influenced by scientific advancement and political turbulence that challenged traditional ways of understanding the physical world.

The Visual Language of Modernity

Let’s look more closely at two modernist painters who use abstract shapes and symbols to represent subjects taken from the world around them.

What symbols do you notice in this painting? What do the colors bring to mind?

Visual elements from the regalia of a soldier’s uniform and military pageantry come together in this abstract portrait of German officer Karl von Freyburg, a close friend of American artist Marsden Hartley. Painted during Hartley’s stay in Berlin (May 1913 to December 1915) as part of the artist’s War Motif series, Hartley represents von Freyburg through symbolic attributes rather than physical features. Bold primary colors of letters, numbers, flags, and geometric shapes commemorate von Freyburg and his military service through coded references, including the number four, the regiment in which he served, and the Iron Cross, a German military award given to soldiers for bravery in the battlefield, positioned at the top of the canvas.

The artist’s personal tribute to von Freyburg, who died in 1914 at the start of World War I, also speaks to Hartley’s experiences of pre-war Berlin during a period of urban transformation. The primary colors and compact composition filled with abstracted objects which appear to be in flux evoke the bright, disorienting lights of street signs and traffic signals. For Hartley, the spectacle and tempo of the modern metropolis was rich with creative material, something that he likens to a display of pageantry in a 1913 letter to American art collector and writer Gertrude Stein:

“There is an interesting source of material here—numbers + shapes + colors that make one wonder—and admire—It is essentially mural this German way of living—big lines and large masses—always a sense of pageantry of living. I like it—.”

In The Iron Cross, allusions to Karl von Freyburg and the artist’s experience of Berlin on the eve of war form a network of symbolic meanings that situate the intimate portrait within the context of technology, war, and the dynamism of urban life.

What similarities and differences do you notice in Marsden Hartley’s portrait of Karl von Freyburg and Thomas Eakins’s portrait of W. D. Marks?

What shapes do you notice? What objects or associations come to mind?

In this Cubist still life a group of objects including a pipe, a glass, a fruit bowl with a cluster of grapes, and the letters J O R are arranged on a wooden table covered with a patterned tablecloth. Many of the objects are depicted from multiple perspectives at once, such as the glass that is rendered volumetrically but seen both from above and straight on. Other items such as the tabletop and fruit bowl appear flat, working against the illusion of three-dimensional depth. The overlapping shapes and planes of black, grey, and ochre color give the illusion of physical objects in space while also calling attention to the flatness of the canvas.

This painting by Georges Braque, an instrumental figure in the development of Cubism, shows the artist’s longstanding interest in still life, a traditional subject matter in Western art depicting inanimate, everyday objects. Painted in 1930, Nature morte et verre returns to Cubist practices from decades earlier when Braque and Pablo Picasso first broke with the tradition of using linear perspective to create the illusion of depth. They applied cultural, intellectual, and scientific advancements such as Albert Einstein’s theory of special relativity to create compositions that appear in constant motion.

For Braque, still life painting explored the material qualities of physical objects and the issue of how to represent these three-dimensional objects on a two-dimensional canvas. Through the combination of volumetric curves and flat planes, Nature morte et verre investigates spatial relationships, evoking a fragmented experience of modern life.

Braque once said that his interest in still life “corresponded to the desire that I have always had to touch the thing, not just to see it.” How does the artist convey the tactile nature of physical objects in Nature morte et verre?

In this video about the past exhibition Georges Braque and the Cubist Still Life 1928–1945, curator Karen K. Butler discusses Braque’s still life in the context of the artist’s career and the start of World War II.

Up Next: Hartley and Braque both employed a visual language that translates the traditional genres of portraiture and still life into a modern context. We now turn to artists whose work was informed by the conditions of wartime Europe that led to violence, destruction, and displacement.

Exile Art

Let’s look more closely at two artists whose paintings directly and indirectly reference the traumatic conditions of World War II.

What associations does this painting bring to mind?

In Golden Brown Painting, abstract shapes cluster around the center of the canvas, recalling a landscape with fluid biomorphic forms that suggest plants, water, and rock formations. The thin washes of warm ochre and shades of green create layered and transparent veils of color that reference the mid-1920s paintings of Spanish surrealist artist Joan Miró.

An Armenian immigrant who fled persecution and ethnic cleansing during the Armenian genocide in Ottoman Turkey, Arshile Gorky settled in the United States in 1920 where he studied European modernist painters. In the 1940s he encountered Surrealist artists displaced from Nazi-occupied Europe such as Roberto Matta, who was also in exile. These artists encouraged Gorky to experiment with Surrealist practices such as automatic painting, which intentionally resisted conscious thought to express unconscious associations, often resulting in uncanny, dreamlike compositions. As in this painting, Gorky painted and drew shapes that combined aspects of dreams and past experiences into the depiction of a subject. He connected his experiences of the American landscape, for example, to his memories of Armenia, writing that “I view nature in America, but memory plays favorites. And for me, that which we had in Armenia had a distinct essence.”

Gorky likely based Golden Brown Painting on the landscape around an abandoned silica mill on the Housatonic River in Connecticut, which he and his wife visited in the summer of 1942. The flowing and indistinct imagery recalls the mutable nature of dreams and memories, engaging with both landscape and abstraction. Influenced by Surrealist techniques of the 1910s and 1920s, Gorky’s energetic brushwork is also seen as a precursor to American Abstract Expressionism of the 1950s, characterized by gestural brushwork that gives the impression of spontaneity.

What remembered landscape does Golden Brown Painting evoke for you? What emotions and memories do you associate with this place?

Spend some time looking at this painting. Notice the figures and the objects in this scene: What do you think is happening?

In this painting by American artist Philip Guston, nine children dressed in masks, crowns, and paper hats play in a dark cityscape that has been transformed into an informal stage. They enact a mysterious narrative, surrounded by lightbulbs, torn newspapers, and dilapidated furniture and architectural details. Though the scene conveys movement through the children’s various actions—pulling on a rope, putting on a blindfold, and ringing a bell—the densely-packed composition creates a sense of immobility, underscored by the dead branches on a central pillar whose binding restricts their growth.

The painting’s title refers to a Mother Goose nursery rhyme, “The Old Woman and the Pedlar” (1917), in which an old woman questions who she is after her appearance is changed without her consent. The unsettling tale’s connection to the narrative depicted in the painting remains enigmatic, though much like nursery rhymes, Guston explored difficult subject matter through the motif of children’s games. In If This Be Not I, references to the current events of World War II—such as the shredded newspapers in the foreground and the boy in striped pajamas lying before a barbed wire fence, an allusion to Nazi concentration camps—situate this painting in the sociopolitical context of wartime Europe.

Guston completed If This Be Not I in 1945, shortly before becoming a professor of art at Washington University in St. Louis. When it was first exhibited in 1945 at Midtown Galleries in New York, If This Be Not I received praise from critics for its formal strengths, including his complex treatment of space, and for its engagement with European avant-garde art such as the work of Max Beckmann, an exiled German artist who would replace Guston on the faculty of the School of Fine Arts at Washington University in 1947. The compressed composition and flattened forms depicted at various angles blur distinctions between figure, object, and setting, demonstrating a shift in Guston’s aesthetics away from figuration and towards abstraction. In the 1950s, a period in which Abstract Expressionism gained critical success in the American art world, Guston turned to complete abstraction, as we see in Fable I (1956–57), one of the artist’s best-known works in the collection of the Kemper Art Museum.

How has your interpretation of this painting changed after learning more about its context?

Notes

Ashton, Dore. A Critical Study of Philip Guston. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

Boone, Emilie. “Spotlight Essay: Thomas Eakins.” In Spotlights: Collected by the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, edited by Sabine Eckmann. St. Louis: Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, 2016.

Butler, Karen K. with Renée Maurer. Georges Braque and the Cubist Still Life, 1928–1945. St. Louis: Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum; Washington, DC: The Phillips Collection; Munich: Prestel–Delmonico, 2013.

Butler, Karen K. “Spotlight Essay: Georges Braque.” In Spotlights: Collected by the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, edited by Sabine Eckmann. St. Louis: Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, 2016.

Coleman, William L. “Spotlight Essay: Thomas Cole.”

Keith, Rachel. “Spotlight Essay: Narcisse Virgil Diaz de la Peña.” In Spotlights: Collected by the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, edited by Sabine Eckmann. St. Louis: Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, 2016.

Marsden Hartley to Gertrude Stein, August 1913, cited in Patricia McDonnell, Dictated by Life: Marsden Hartley's German Paintings and Robert Indiana's Hartley Elegies. Minneapolis: Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum, University of Minnesota, 1995.

Murawski, Michael. “Spotlight Essay: Marsden Hartley.” In Spotlights: Collected by the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, edited by Sabine Eckmann. St. Louis: Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, 2016.

Letter from Thomas Cole to Robert Gilmor, May 21, 1828, as quoted in Louis Legrand Noble, The Life and Works of Thomas Cole, ed. Elliot S. Vesell. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1964.

Tinterow, Gary, Lisa Mintz Messinger, and Nan Rosenthal, eds. Abstract Expressionism and Other Modern Works: The Muriel Kallis Steinberg Newman Collection in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art Publications, 2007.

Thomas Cole (American, b. England, 1801–1848), Aqueduct near Rome, 1832. Oil on canvas, 44 1/2 x 67 5/16". University purchase, Bixby Fund, by exchange, 1987.

Narcisse Virgile Diaz de la Peña (French, 1807–1876), Wood Interior, 1867. Oil on canvas, 43 1/4 x 51 1/2". Bequest of Charles Parsons, 1905.

Thomas Eakins (American, 1844–1916), Portrait of Professor W. D. Marks, 1886. Oil on canvas, 76 3/8 x 54 1/8". University purchase, Yeatman Fund, 1936.

Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida (Spanish, 1863–1923), ¡Otra Margarita! (Another Marguerite!), 1892. Oil on canvas, 51 1/4 x 78 3/4". Gift of Charles Nagel Sr., 1894.

Marsden Hartley (American, 1877–1943), The Iron Cross, 1915. Oil on canvas, 47 1/4 x 47 1/4". University purchase, Bixby Fund, 1952.

Georges Braque (French, 1882–1963), Nature morte et verre (Still Life with Glass), 1930. Oil on canvas, 20 3/16 x 25 5/8". University purchase, Kende Sale Fund, 1946.

Arshile Gorky (American, b. Armenia, 1904–1948), Golden Brown Painting, 1943–44. Oil on canvas, 43 13/16 x 55 9/16". University purchase, Bixby Fund, 1953.

Philip Guston (American, 1913–1980), If This Be Not I, 1945. Oil on canvas, 42 1/4 x 55 1/4". University purchase, Kende Sale Fund, 1945. The painting was recently restored with funds from the Guston foundation.

All artworks are copyright the artist or the artist’s estate unless otherwise specified. Images on this tour are for educational purposes only and are not licensed for commercial applications of any kind.

We are committed to encounters with art that inspire creative engagement, social and intellectual inquiry, and meaningful connections across disciplines, cultures, and histories. Do you have ideas or suggestions for other learning resources? Is there an artist or topic that you would like to learn more about? We would love to hear your feedback. Please direct comments or questions to Meredith Lehman, head of museum education, at lehman.meredith@wustl.edu.

.png)