Catharina Manchanda

Jon and Mary Shirley Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seattle Art Museum

Formerly curator at the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum

Images appropriated from movies, advertisements, and stock photography have been the source material for much of John Baldessari’s art since the 1970s. How visual conventions—old and new, painterly, photographic, and filmic—inform the way we interpret images is a central question posed by his work. Baldessari not only investigates how formal devices reinforce the narrative content of an image or image sequence but also asks us to consider the ways in which images circulate in our mediated environment.

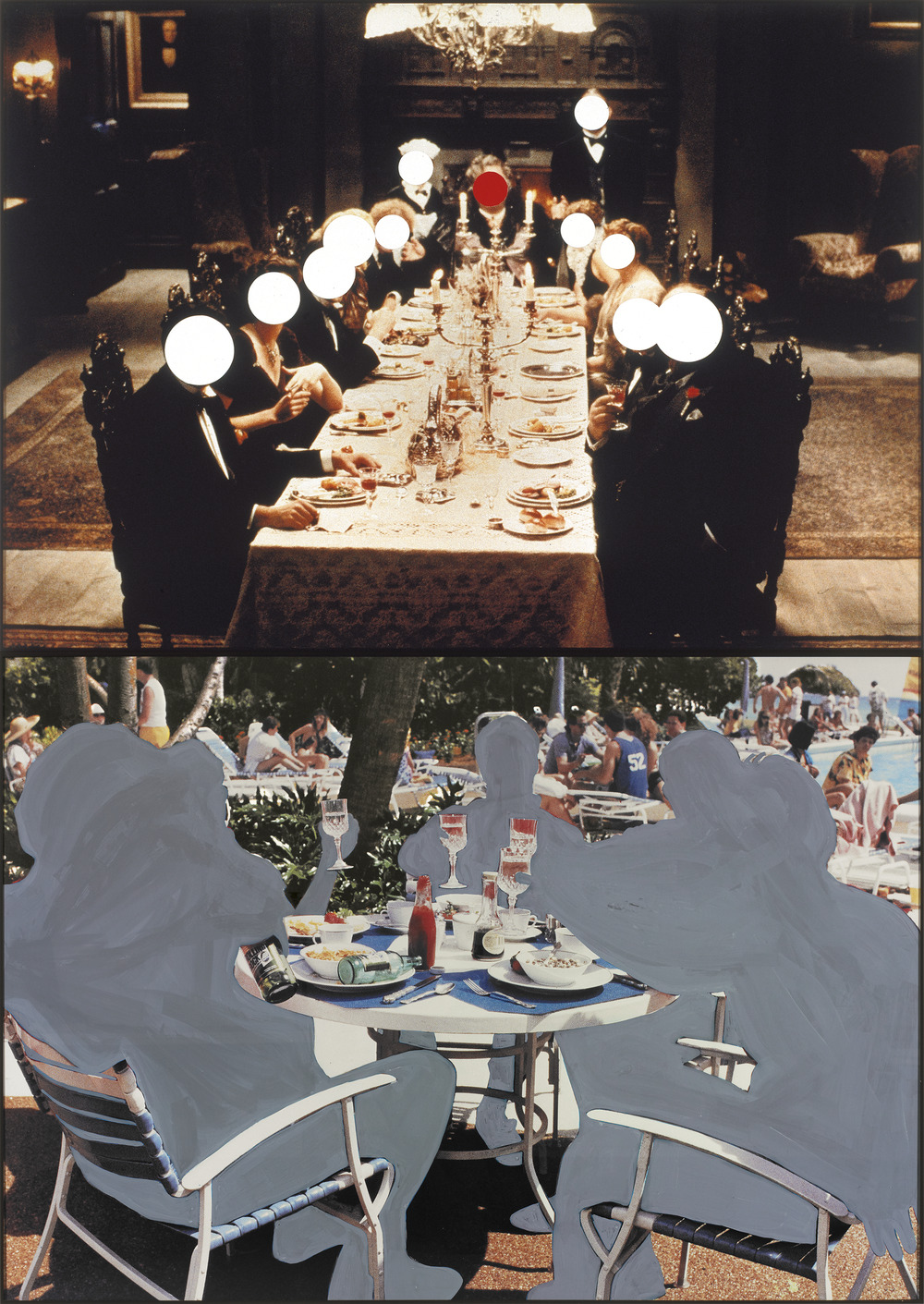

The vertically stacked diptych Two Compositions (Formal / Informal; Interior / Exterior) reexamines the conventions of group portraiture.1 Rather than commemorating an occasion or event, Baldessari here focuses on the pictorial strategies that communicate class, rank, and authority among members of a social group. In the upper image, the artist presents us with a long table, around which are seated a group of elegantly dressed dinner guests whose faces are obliterated by monochromatic circles of paint; in the lower image, he likewise manipulates a scene by painting over the entire bodies of a group seated outdoors at a poolside table. Baldessari introduced these invasive obliterations in the mid-1980s, following a decade in which he explored the relationship between image sequences and sentence structure.2 Painterly obliterations overlaid onto photographic images provided an opportunity to intervene within the structure of the image, and he has used them ever since.

In Two Compositions (Formal / Informal; Interior / Exterior), Baldessari’s cancellations not only render each figure anonymous but also prompt us to consider the social inflections of the settings, in this case a formal dining room and a casual outdoor scene. His painterly interventions also draw attention to how such details as facial expressions, gazes, body language, and dress function as markers of both individuality and meaning in portraiture, as well as how settings communicate issues of social class. The painted portrait in a gilded frame in the upper left corner of the top photograph, for example, is instrumental in conveying an air of aristocratic class, which is reinforced by the elegant dress of the guests around the table, the fine dinnerware, tablecloth, and candles. By contrast, the visual language of the lower image is marked as “informal,” an exterior scene with bathers in the background, in which our attention is directed at the surroundings: the plastic chairs, the ketchup bottle, and the incongruously elegant glasses.

Representations of class, social status, and rank, as much as the role of hand gestures and facial expressions as a means of communication, are rooted in the visual conventions of group portraiture. While the individual portrait is traditionally charged with conveying a likeness of the sitter as well as a psychological resonance that reveals the person beneath the mask, the group portrait is concerned with group identities—a family, an institution, a professional circle. It serves as a vehicle to communicate social values or a group’s civic responsibility and power. Social hierarchies and economics traditionally determine who assumes a prominent place within the portrait and who is assigned a marginal role. Dress, setting, and accessories convey information about the individual as much as the social status of the group as a social unit. These are also the formal strategies that Baldessari has consistently investigated and disrupted in his work. The painted areas are abstract and flat, disrupting the coherence of the scene and puncturing its perspectival space. The colored dots that cover the faces in the upper image of Two Compositions not only map the logic of perspective, with the red one designating the vanishing point, but also indicate a social hierarchy—in this case, rendering visible how the perspective highlights the person at the head of the table. By contrast, the abstract gray paint that covers the figures of the seated group in the lower image removes the boundaries between the individual figures to create larger, undefined shapes. In this case, Baldessari does not stress hierarchical differences between figures but the cohesion of the group as a social unit.

Baldessari’s interest in how images convey meaning reaches back to his artistic beginnings as a conceptual artist in the 1960s. At that time the photograph’s relationship to “the real” and to interpretive frameworks was of particular interest to a number of American and European artists, including Baldessari, Robert Barry, Jan Dibbets, Hans-Peter Feldmann, and Douglas Huebler. Much of the work of photo-conceptual artists in the late 1960s centered on the presumed objectivity and accuracy of the photographic image, which they upended through image sequencing or the pairing of seemingly incongruous images and titles.3 In contrast, Baldessari used nondescript photographs and art historical texts to disrupt the pictorial conventions and values that were taught in art schools or communicated through photography manuals.4 In the 1970s he became increasingly interested in popular culture images—for instance, advertisements and movie stills that traditionally operate in a different context—and the associations that arise from arranging two or more unrelated images in sequences. In the 1980s he frequently used movie stills as source material for his work, and this is the case with Two Compositions.5 While a photograph, like a painting, is traditionally meant to be viewed, studied, shared, and displayed on its own, a film still, in contrast, is a split-second frame that is part of the flow of a larger narrative, usually accompanied by sound and not seen by itself. By “halting” the movie, the artist is asking us to read the film stills as photographs, shifting our approach and expectations. In doing so, he returns our attention to those signs and gestures that are indebted to painterly and photographic conventions—conventions that communicate meaning on a purely visual level.

In the end Baldessari underscores the importance of reading the literal information in the image against a cultural and contextual framework, and he does so by eluding narrative interpretation. Neither his two images nor his title gives us any indication of who the people are or what occasion brings them together. Are we looking at “real people” or actors? Are these actual representations of social gatherings, or scenes staged for a movie or advertisement? This uncertainty fundamentally affects our interpretation of the images, reminding us that we are dealing with a mediated and fragmented reality. The pictures we see refer back to a narrative context—a news story, a film, an advertisement, or possibly an account of history—that we can no longer reconstruct.

- 1 The group portrait gained particular prominence in seventeenth-century Holland. For a detailed history and analysis of the genre, see Harry Berger Jr., Manhood, Marriage, and Mischief: Rembrandt’s “Night Watch” and Other Dutch Group Portraits (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007).

- 2 For example, in Baldessari’s artist’s book Brutus Killed Caesar (1976), each spread consists of three photographs that echo the three-word structure of the title. On the left and right we see profile views of two men who are “looking at each other.” These portraits remain constant throughout the book; what changes is the image between the two men. The first sequence reads like a rebus—portrait-knife-portrait—but subsequent examples offer different, often humorous interpretations, as the knife is replaced by images of a gun, a coat hanger, a banana peel, a potted plant, and a can of paint, among other items.

- 3 In 1969 Robert Barry famously photographed gas containers in a landscape. The photographs had titles such as Inert Gas Series: Helium. Sometime during the morning of March 5, 1969, 2 cubic feet of Helium will be released into the atmosphere. According to the title, the image documents an empirical act; the pun centers on the fact that gas is invisible to the eye—the eye of the camera as much as the eye of the viewer.

- 4 A good example is Baldessari’s 1967 series of photo-transfer paintings. Wrong (1967) shows a snapshot of the artist standing in front of a palm tree that looks as if it is growing out of his head; the stenciled caption below the image reads “wrong” and follows the pattern of photography manuals that illustrate “good” and “bad” composition. With this series, Baldessari positioned himself against such conventions, further distancing himself from expectations of artistic craftsmanship by having a friend take the photograph and hiring a sign painter to stencil the caption below the image. These photo-transfer works should be seen in context with his text paintings, white canvases on which he had a sign painter stencil phrases such as “Everything is purged from this painting but art, no ideas have entered this work” (1967–68).

- 5 The top image is from the film Haunted Honeymoon (1986); the bottom is from the film Revenge of the Nerds II: Nerds in Paradise (1987). Thanks to Allison Unruh for bringing this to my attention.