Martín Chambi and Edward Sheriff Curtis

Photography Gallery

Martín Chambi (1891–1973) and Edward Sheriff Curtis (1868–1952) carried out influential photographic practices at different latitudes of the Americas in the early twentieth century. Chambi operated a studio in Cusco, Peru, from 1923 to 1950, specializing in Andean landscapes and portraits of people from a variety of social classes and ethnicities. Curtis traveled the United States from 1906 to 1930 with ethnographic ambitions to document Native American nations. The juxtaposition of their work here creates a context for the investigation of and dialogue about the photography of Indigenous communities in relationship to processes of colonialism, modernization, and urbanization in the Americas.

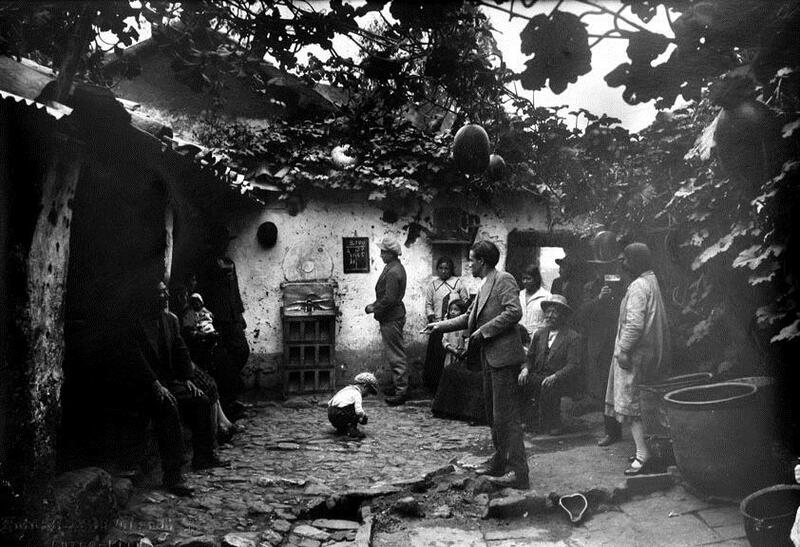

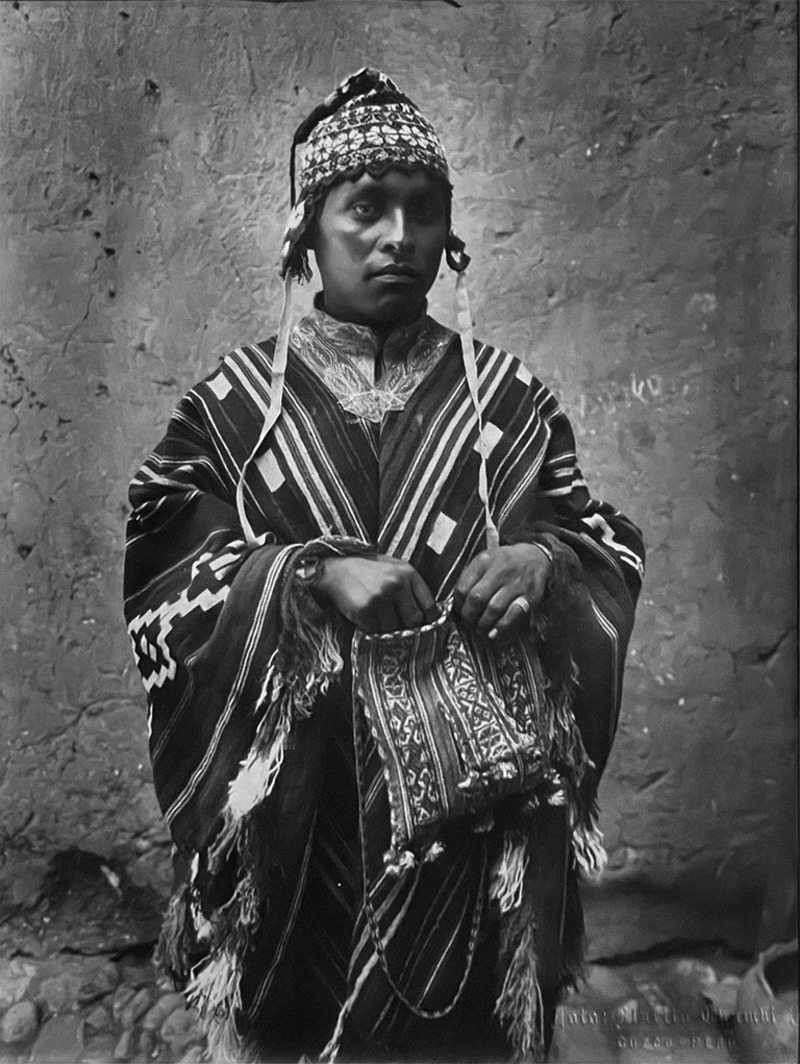

The photographs by Chambi include images of Indigenous people around Cusco in moments of leisure as well as posed portraits. Born in a rural province to Quechua parents, Chambi spoke both Quechua and Spanish, allowing him to connect with many of his photographic subjects. He embraced Andean culture and identity as a subject, but his photographs notably focus on the present, exploring Indigeneity in relationship to technology, global cultures, and social change, rather than a romanticized past.

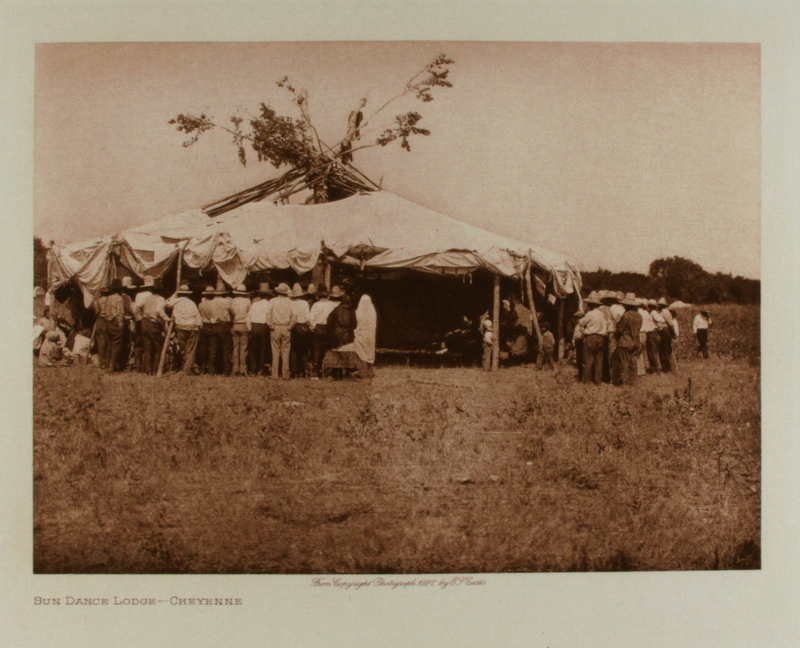

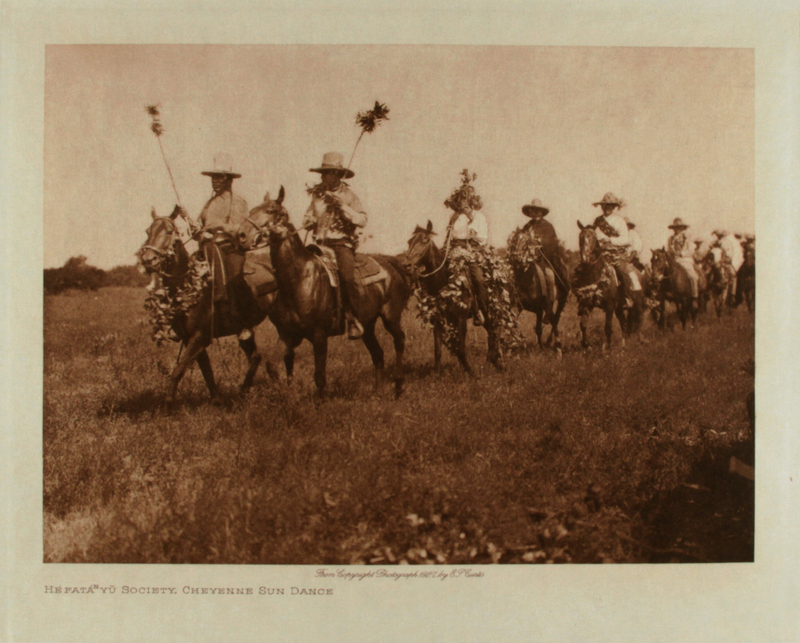

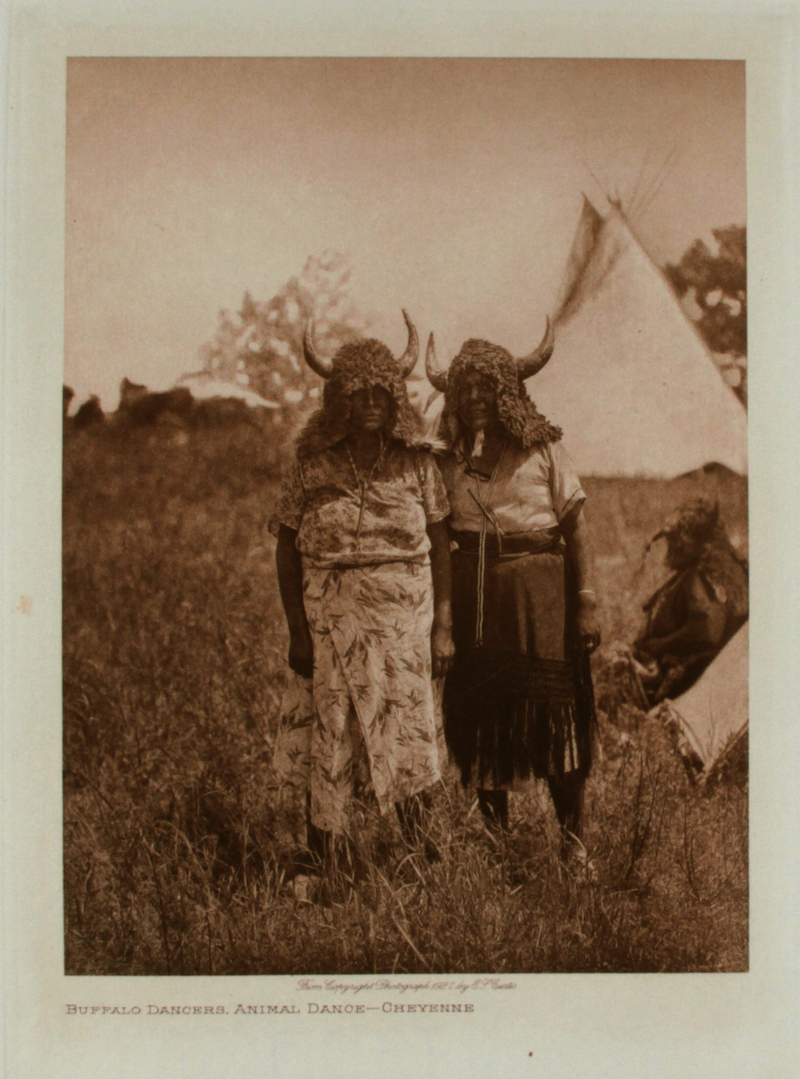

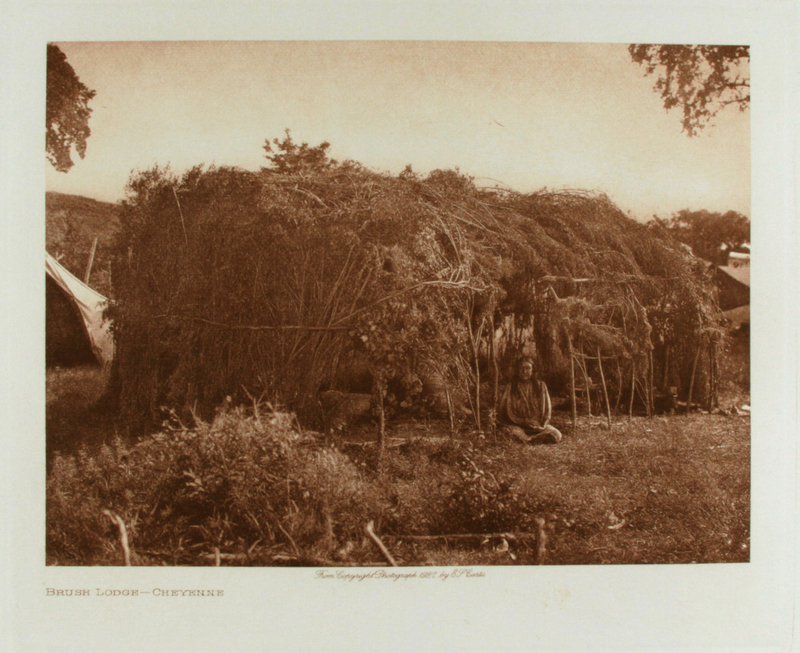

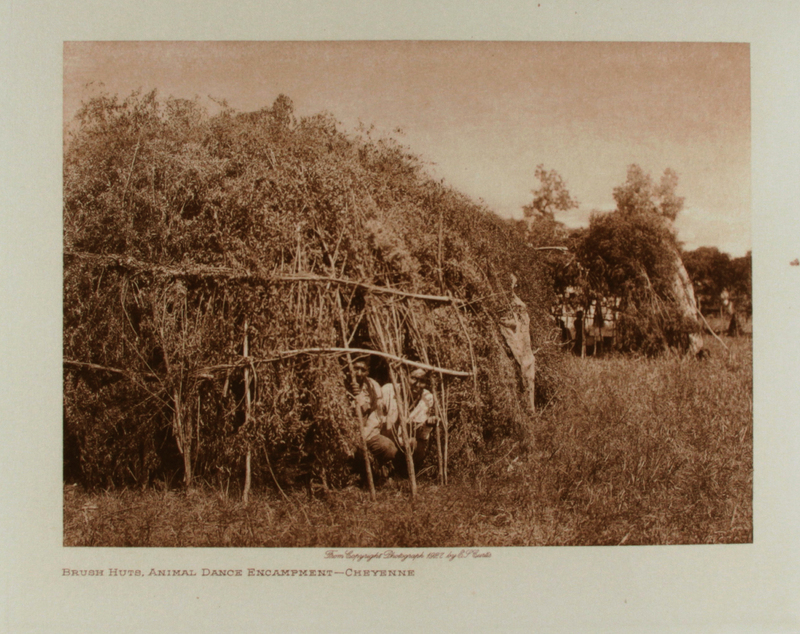

The photographs by Curtis, printed in the penultimate volume of his influential book The North American Indian, depict people from the Southern Cheyenne (Tsistsistas) tribe in Oklahoma in the late 1920s. Today the Southern Cheyenne share a government with the Arapaho in western Oklahoma. Curtis’s project illustrates the conflicted nature of photography—part science, part art—in a period when anthropology was also becoming a formalized discipline. Although the ethnographic texts of Curtis’s book suggest documentary aspirations, his stylized photographs are mediated through a colonialist framework and nostalgia for preindustrial life. He framed Indigenous communities as cultures in the process of disappearing, while erasing the conditions of their displacement and genocide.

Selected works

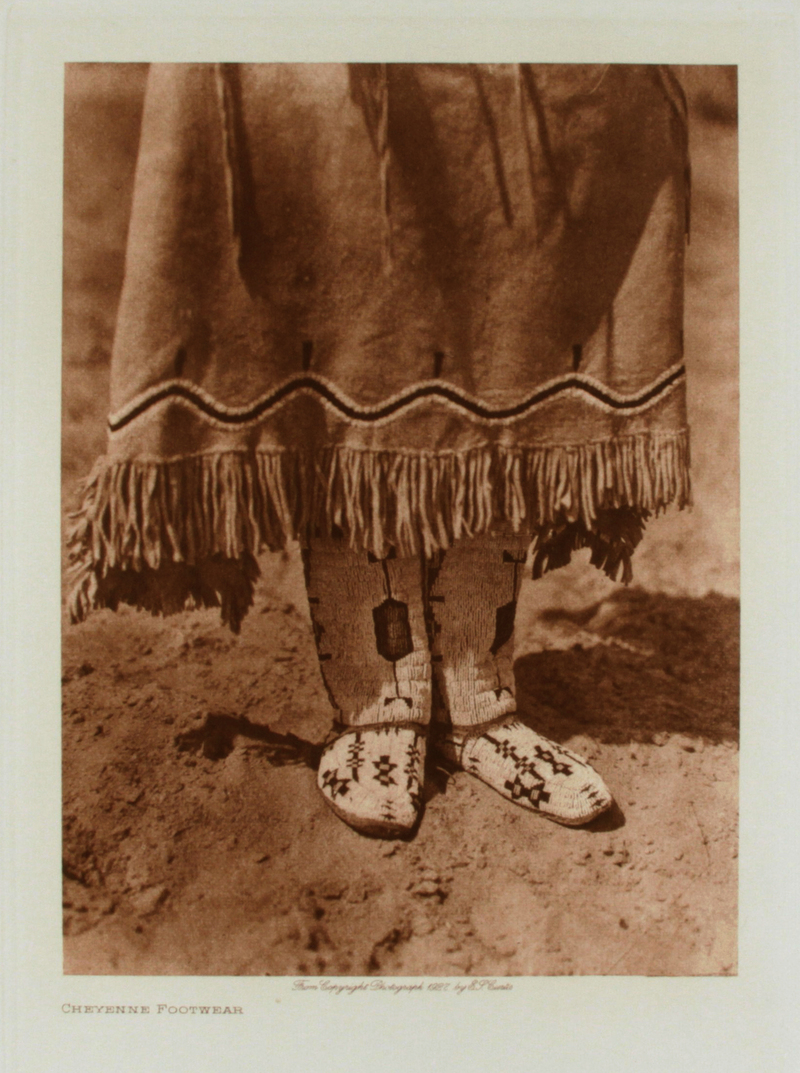

Edward Sheriff Curtis

Cheyenne Footwear

1927

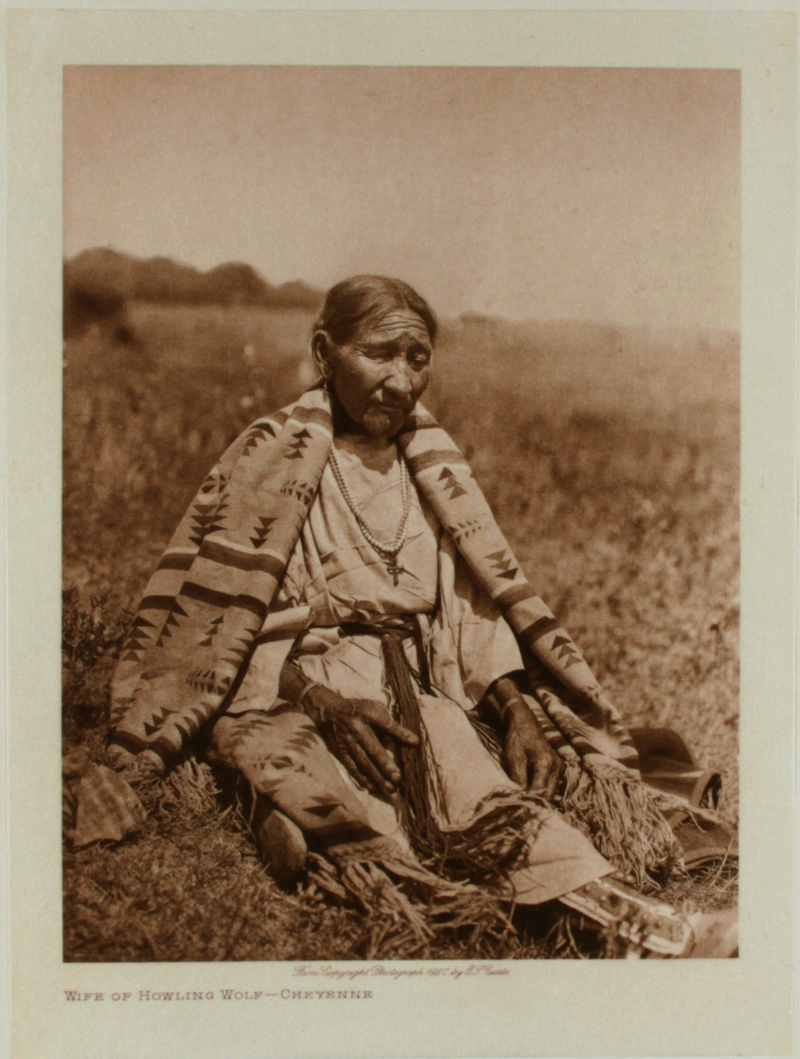

Edward Sheriff Curtis

Wife of Howling Wolf—Cheyenne

1927

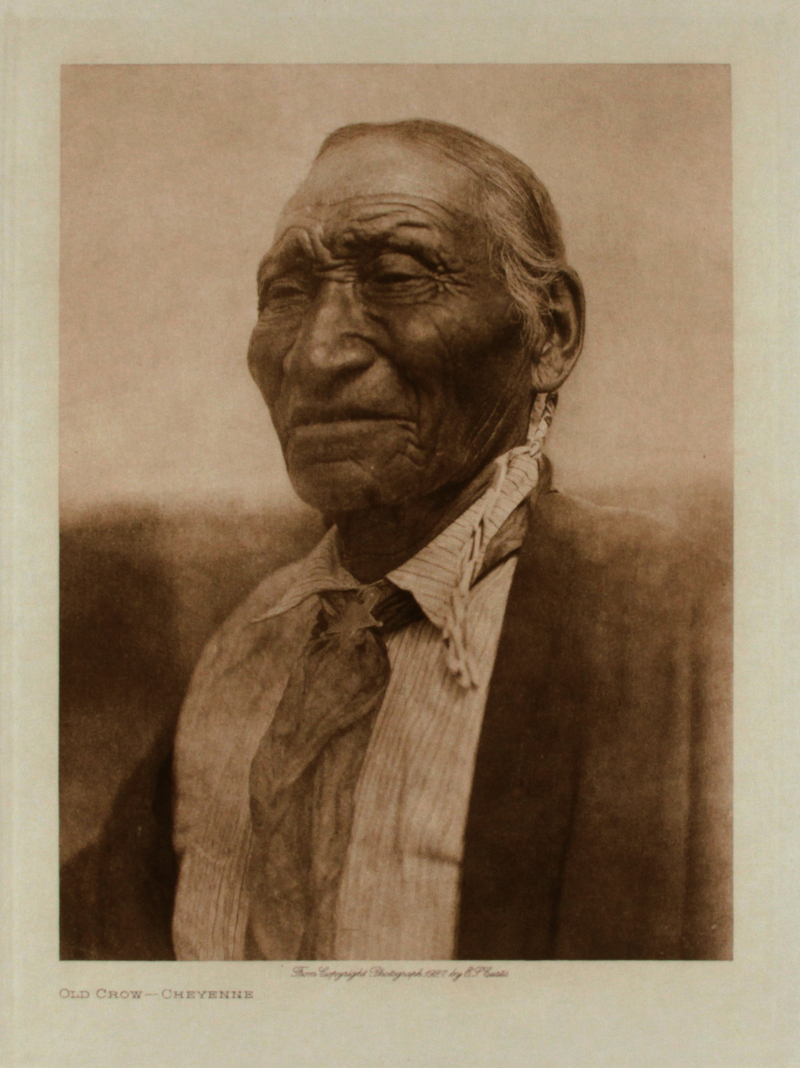

Edward Sheriff Curtis

Old Crow—Cheyenne

1927

Edward Sheriff Curtis

Sun Dance Lodge—Cheyenne

1927

Edward Sheriff Curtis

Hefata"yu Society, Cheyenne Sun Dance

1927

Edward Sheriff Curtis

Buffalo Dancers, Animal Dance—Cheyenne

1927

Edward Sheriff Curtis

Drying Meat—Cheyenne

1927

Edward Sheriff Curtis

Brush Lodge—Cheyenne

1927

Edward Sheriff Curtis

Brush Huts, Animal Dance Encampment—Cheyenne

1927

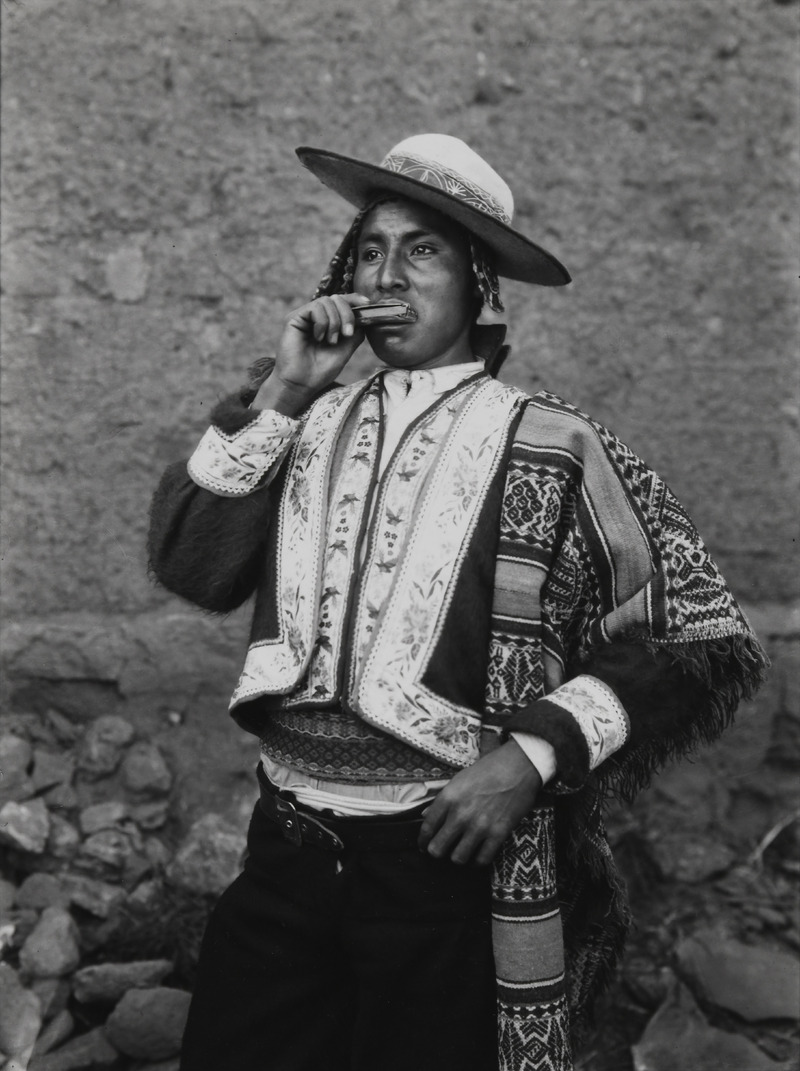

Martín Chambi

Fiesta en la Hacienda Angostura (Celebration at the Hacienda Angostura)

c. 1929, printed later

Martín Chambi

Jugando al sapo en chicheria, Cusco (Playing sapo in a chicheria)

1931, printed later

Martín Chambi

Juan de la Cruz Sihuana, Cusco (formerly known as "Gigante de Paruro" [Giant of Paruro])

c. 1925–29, printed later

Martín Chambi

Campesinos en el juzgado, Cusco (Campesinos in court, Cusco)

1929, printed later

Martín Chambi

Untitled

c. 1930s, printed later

Martín Chambi

Campesino con chuspa (Peasant with coca bag)

1934, printed later

Martín Chambi

Untitled

c. 1930, printed later