Balancing Acts

Combine art and engineering to create a sculpture that responds creatively to design problems.

Download the Balancing Acts educator resource:

Materials

- Cardstock

- Scissors

- Stapler

- Wire

- Small objects of different sizes, such as beads

Part I

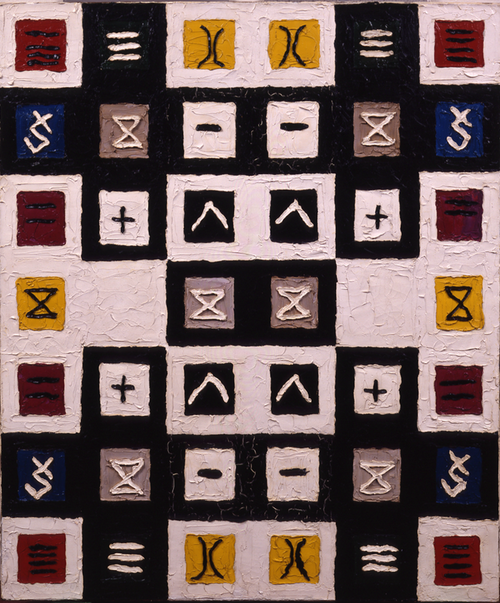

Spend a minute looking closely at this sculpture titled Rumor of Limits #4, made by the Spanish artist Eduardo Chillida in 1960.

What do you notice about this sculpture?

What materials do you think it is made of? How do you think the artist sculpted it?

What do you notice about how this sculpture balances?

Eduardo Chillida (1924–2002) is known for creating abstract sculptures that investigate space, form, and borders. He was born in the Basque region of northern Spain and studied architecture in Madrid before moving to Paris to study art. When Chillida returned home, he learned to forge iron from local blacksmiths and had a forge installed in his studio. He began to sculpt mostly in iron, wood, and steel, materials from the Basque region that he saw as representing his homeland’s traditions and landscape. For Rumor of Limits #4 Chillida transformed a sheet of iron—an extremely heavy and hard material—into a three-dimensional sculpture with a sense of movement and lightness by cutting and bending the heated metal. The work is part of a multi-year series of sculptures exploring what the artist called “inner space.” Chillida also used paper as a material to explore his ideas and questions about form and space, creating engravings, drawings, and collages alongside his sculptures.

Like Chillida, let’s start with a flat two-dimensional sheet and transform it into a dynamic three-dimensional sculpture that balances on the ground.

Design problem: Create a three-dimensional sculpture that balances on a flat surface. Materials are limited to a single piece of cardstock, scissors, and a stapler. Additionally, the cardstock should be kept intact as a whole sheet and not cut up into smaller pieces.

Experiment with different ways of tearing, cutting, stapling, folding, and rolling your cardstock to make a three-dimensional balancing sculpture. Spend a few minutes sculpting, then check that your sculpture satisfies the design problem. Can it balance on a flat surface? If not, adjust your sculpture to increase its stability. When you are satisfied with your sculpture, set it aside.

Part II

Now that you’ve experimented with transforming a flat sheet of paper into a three-dimensional standing sculpture, let’s look at how another artist creates balance in his moving sculptures.

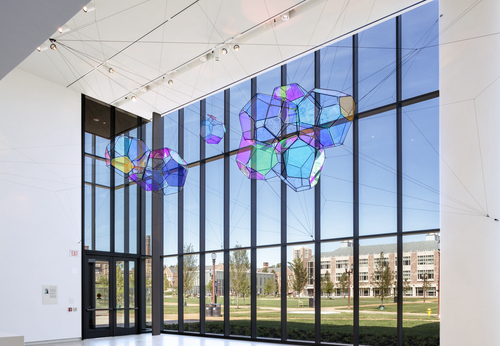

Spend a minute looking closely at this sculpture titled Bayonets Menacing a Flower, made by the American artist Alexander Calder in 1945.

What do you notice about this sculpture?

What materials do you think it is made of? How do you think the artist sculpted it?

What do you notice about how this sculpture balances?

Alexander Calder (1898–1976) made sculptures that explore movement and balance. Calder studied mechanical engineering before later deciding to become an artist. His interest in movement led him to begin using motors to create kinetic sculptures that moved. He stopped using motors in his art when he realized that he could make balanced hanging sculptures that move slowly in response to air currents. These hanging sculptures that are set in motion by currents of air are called “mobiles.” Calder also made stationary sculptures that stand on the ground, which he called “stabiles,” and a third category of sculptures called “standing mobiles” that fall somewhere in between, combining the stationary structure of the stabile with the moving elements of the mobile. Calder’s exploration of physical movement in sculpture inspired many other artists, including Eduardo Chillida, who created a hanging mobile sculpture to honor Calder after his death.

Bayonets Menacing a Flower is an example of a standing mobile. Calder bolted together spikey pieces of painted sheet metal to create a three-dimensional standing form, and then rested a long wire with small disks of metal on either end across this base. The mobile part of the sculpture made from wire is not attached to the metal structure and relies on the artist’s understanding of balance to stay in place as it gently sways in the air. Like Calder, let’s explore how to add a mobile component to our standing sculpture while maintaining its balance.

Design problem: Add a mobile component to your standing sculpture while maintaining its balance. Use wire to make a mobile component that suspends small objects like beads or cut-paper shapes of different sizes on either end. The mobile component should balance on the standing sculpture, and your new standing mobile should not tip over when placed on a flat surface.

Spend about 10 minutes adding the mobile component to your sculpture. Don’t be discouraged if your sculpture tips over; trial and revision are important parts of the design process!

Test the balance and sturdiness of your standing mobile with tip and wind tests. See what happens when you gently nudge and blow on your sculpture. If it loses balance and falls over easily, make changes to your sculpture to increase its balance and stability.

When your sculpture is complete, reflect on your design process:

What challenges did you encounter while creating your sculpture, and what changes did you make to your design to address those challenges?

Notes

“Biography.” Eduardo Chillida, www.eduardochillida.com/en/artist/photobiography.

“Eight Studio Habits of Mind.” Project Zero, Harvard Graduate School of Education. https://pz.harvard.edu/resources/eight-habits-of-mind.

“Eduardo Chillida.” Hauser & Wirth, July 10, 2023, www.hauserwirth.com/artists/2864-eduardo-chillida/.

Essex, Meredith. “Sculpture in Balance.” Arts Impact. Lesson. https://arts-impact.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Sculpture-in-Balance-6-17-16.pdf.

“Introduction.” Calder Foundation, calder.org/introduction/.

Müler, Markus, ed. Eduardo Chillida. Münster: Kunstmuseum Pablo Picasso Münster, 2011.

“Who Is Alexander Calder?” Tate, www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/alexander-calder-848/who-is-alexander-calder.

Eduardo Chillida (Spanish, 1924–2002), Rumor de limites #4 (Rumor of Limits #4), 1960. Iron, 38 1/8 x 38 1/8 x 26 1/4". Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Richard K. Weil, 1962. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VEGAP, Madrid.

Alexander Calder (American, 1898–1976), Bayonets Menacing a Flower, 1945. Painted sheet metal and wire, 45 x 51 x 18 1/2". University purchase, McMillan Fund, 1946. © Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

We are committed to encounters with art that inspire creative engagement, social and intellectual inquiry, and meaningful connections across disciplines, cultures, and histories. Do you have ideas or suggestions for other learning resources? Is there an artist or topic that you would like to learn more about? We would love to hear your feedback. Please direct comments or questions to Meredith Lehman, head of museum education, at lehman.meredith@wustl.edu.